[ad_1]

When I met Stanley Crawford in 2005, he was, by the estimation of my twenty-three-year-old self, already old. I was working at the reception desk of the chaotic Soho offices of the Overlook Press when Stan, a gray-bearded giant (at 6’3″) with wiry frame and impossibly weathered skin, strode into my life. I can’t, and probably don’t want to, recall what I said to him in that meeting. But I vividly remember his facial expression, which I would come to learn was sort of his default: a judgmental cocked eyebrow perched on a weary forehead, framing eyes that simultaneously looked right through me and welcomed me into a private joke.

Little did I know then that my curiosity about this striking character would open up a relationship that would extend over the next nineteen years, a period that would become some of the most productive years of Crawford’s nearly six-decade career as a writer. When Stan died at the age of 86, shortly after a cancer diagnosis in late January of this year, he had authored nine novels and four works of nonfiction; four of those novels and his final work of nonfiction were published in the last decade of his life.

Stan had every reason to be wary of, and amused by, me and the company where I worked. A newly minted English major from Oklahoma, I had recently been hired at Overlook as a receptionist/editorial assistant. Overlook, at the time, was staffed by an unbelievable cast of underaged literary ne’er do wells (then-aspiring novelist Ottessa Moshfegh worked as a production assistant at the desk behind me) working under its famed and aged publisher, Peter Mayer.

Peter, belching clouds of Pall Mall smoke and a steady stream of angry profanity from his corner office, oversaw the heroic if haphazard work of keeping Overlook afloat. A list of Sudoku paperbacks and judiciously selected children’s reprints allowed us to continue publishing books like Stan’s fifth novel, Petroleum Man, an ingenious satire of U.S. car culture that had been “overlooked” by our corporate competitors.

Petroleum Man sold a few thousand copies, and earned a respectable bevy of reviews in the alternative and literary press, though it deserved more. It would be the last book Stan published with a New York house.

In many ways, Stan was an archetypal “misfit” victim of the trends in literary publishing analyzed by Dan Sinykin in Big Fiction: How Conglomeration Changed the Publishing Industry and American Literature. With the industry being overtaken by reliable earners like genre novels with “formulaic plots and on-going series that had predictable, built-in sales,” Stan’s unbrandable books were not long for the mainstream publishing world.

With the industry being overtaken by reliable earners like genre novels with “formulaic plots and on-going series that had predictable, built-in sales,” Stan’s unbrandable books were not long for the mainstream publishing world.

But back home in Dixon, the small village in Northern New Mexico where he and his family had settled in 1969, Stan’s work proceeded apace, and our relationship blossomed. As my career took me from my dalliance with publishing to a teaching job in Morocco and finally back to the Southwest for a career as a critic and professor, I kept in touch with him via hundreds of emails and near-annual and often self-invited visits to his farm.

On those magical trips, I made dubious contributions to the work of the farm and the editing of Stan’s books while enjoying afternoons swimming in the Rio Grande and long evenings of good food and conversation in the adobe farmhouse the Crawfords built themselves.

The generosity of Stan and his wife, journalist and dramatist RoseMary Crawford, provided a center in my literary life. Across our forty-four-year age difference, Stan and I shared a rare combination of traits that brought us together: a cosmopolitan sensibility born of years spent abroad, and a love of the cultural and ecological life of our region.

Long before I met him, Stan’s career had taken on a unique trajectory shaped by these sometimes contradictory attributes. His sublimely strange early fiction, especially his third novel, The Log of The SS The Mrs Unguentine, published in 1972, earned him accolades from critics and the admiration of readers of experimental fiction around the world. With the publication of Mayordomo in 1988, he also established a parallel reputation as a regional writer focused on his life as a garlic farmer.

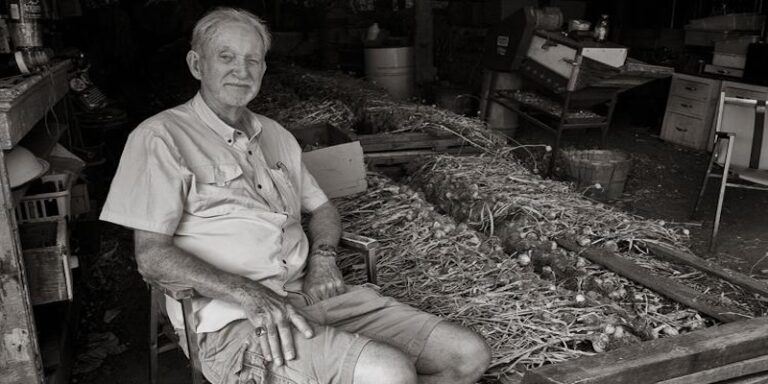

Stan’s life as a farmer was easy to romanticize and celebrate from the outside. Over the course of the time I knew him, he patiently entertained a steady stream of journalists and fans, working for publications ranging to the smallest zines to the New York Times, all dropping in for the weekend to write more-or-less the same article about the charmingly ramshackle farm of the Back-To-The-Lander who had refused to give up.

As Crawford’s reputation as a farm writer was thus maintained, reprints of his early novels appeared steadily over the course of the last twenty years, leading to bursts of laudatory pieces about his early fiction in the literary press. “How does it feel to be a writer destined to be continually rediscovered?” Bomb asked Crawford in 2014.

“Books are like children, and when one is ‘rediscovered’ I’m very happy for it,” he replied. “The writer who wrote it, however, is long gone, has moved on to other things….” While his early work was being perennially rediscovered, Stan labored at those “other things,” often in near obscurity, producing remarkable books for small publishers that weren’t easily assimilable into existing understandings of his writing.

The last decade of Stan’s life was in fact shaped by the tremendous strain of keeping his farm afloat. Global competition from huge corporate conglomerates employing questionable labor practices were depressing the price of his once-niche primary crop. Stan’s last farming book, The Garlic Papers: A Small Garlic Farm in the Age of Global Vampires, chronicles the legal maneuvers Crawford and a lawyer friend used to fight back against his corporate competitors. In chronicling this losing fight, it offers a clear-eyed and devastating portrait of the economics of a twenty-first-century small farm that provides a crucial coda to the localism of his earlier work.

These circumstances on the farm, in addition to the tragedy of losing RoseMary to a long struggle with Alzheimer’s disease, make the great literary achievement of Crawford’s final years—his novels—all the more remarkable.

Stan’s early and mid-career novels focus on the machinations of what novelist Ben Marcus called “patriarchs who show their love through radical inventions and the construction of ingenious, if useless, systems.” His late work breaks opens the aperture on his novelistic vision, abandoning this mode of autocritique to take in a broader range of human responses to life in the shadow of catastrophe.

A passage from the final chapter of The Canyon, his quiet 2015 coming-of-age novel, exemplifies this shift. In this moment, the protagonist Scotty yearns for a future that he imagines as

a blinding white cloud into which all possibilities were diffused. Everything would be different despite the daily evidence to the contrary, in the leisurely yet somehow rigid routine of each day, from the moment the morning sun pried its way through the crack under my door and the rising heat in the upstairs drove me from my flannel sleeping bag and its rich exaltations of bodily fragrances, through the predictable steps of breakfast, the cold sand of the beach spraying over bare feet in the morning, and the rising heat of the afternoon, the midafternoon thunderheads that occasionally delivered brief shower and rare downpours, the slow fall into darkness.

In Crawford’s late style, the future is debilitating to ponder; the novel’s sensual pleasure emerges in the quotidian experiences that pass by almost unnoticed by its narrator before “the slow fall into darkness.” This is true even in Crawford’s most harrowing novel, Intimacy, which traces the everyday routines of an impossibly atomized corporate worker as he ponders suicide: the intimacy of the title is found in the protagonist’s sensory relationship with his carefully curated life with things.

Village (2017), Crawford’s only novel set in New Mexico, abandons the claustrophobic interiority of Intimacy to revel in the lives of a diverse ensemble of eccentric village dwellers. Their lives intertwine with the rhythms of their ecological setting to produce the pseudonymous village of San Marcos (a thinly veiled Dixon) as a living creature itself:

By four the moon would be down or obscured by clouds moving in from the west. The sky would darken. A great collective snoring would rise within the adobe houses and mobile homes of San Marcos. Then the coyotes would sing and chatter from the tops of the clay cliffs as their night, which is their workday, came to a close….Dogs below would howl in response, plaintive and unsteady, admitting a kinship like none they had with the other creatures who slept inside houses, on mattresses, under blankets.

This focus on this threshold between the human and natural worlds also shapes Crawford’s 2015 Seed, arguably the triumph of his late fiction. Seed’s geriatric protagonist Bill Starr, narrating in a voice eroded by encroaching dementia (and crafted during the years that Crawford was wrestling with RoseMary’s diagnosis), comes to speak to something existential. In a moment of lucidity late in the book, Bill ponders his end: “Will there or will there not be a final revelation? Maybe, maybe not….” He looks for this revelation in the act of giving away his possessions to family, even as he is increasingly incapable of finding significance in his gifts, or even remembering them at all.

In the poetic conclusion to A Garlic Testament, Crawford compares the act of storytelling to “our seed, our clove, our filament cast toward the future.” Bill, though, expresses some doubts about his own “seed” as a metaphor for future possibility: “I will go down with pouches brimming with sperm,” he ponders one evening. “Amazing. Unless the little fuckers have already given up the ghost.” The real gift Bill has to bestow to his loved ones is not a story per se but an assemblage of hilarious and poetic meditations on his ever-renewing present.

In my last few months of correspondence with Stan, we were mired in concerns about his latest novel manuscript. Our letters ranged across our usual terrain: questions of character development and plotting, laments about a lack of responsiveness from agents and editors. But at the margins, another story was weaving its way in: Stan, who was fit enough to beat me at ping-pong at age eighty-two and never dwelt on such matters, was starting to remark on disquieting and unexplained health events.

These unusual asides were enough to make me decide to visit him at Colorado College in October, where he was teaching a class on Southwestern literature. I talked to his students about his farm writing; we discussed the increasingly grim state of global affairs over lunch. When we finished, he made an uncharacteristically abrupt announcement that he would be driving back to Dixon for the weekend. He wasn’t himself.

I spent the night I learned Stan had passed poring over the drafts of his last manuscript, looking, I guess, for that final revelation.

It was the last time I saw him. One evening in early January I received a rare text from him: “Turns out I have terminal cancer. Gimme a call.” The call was tough: in our masculine embarrassment, we fell back into the usual day-to-day of our work together, discussing an essay I had just finished about his farm. I said goodbye; he said “talk to you soon.” He was gone days later.

I spent the night I learned Stan had passed poring over the drafts of his last manuscript, looking, I guess, for that final revelation. Tentatively entitled The Stream, it opens with its narrator’s artistic and sexual awakening in Crete, where Crawford lived as an expatriate writer in the late 1960s, and concludes with the narrator as an old man pondering mortality in Dixon. I hope to see it published someday, but it feels like a work in progress; it resists any revelations.

One detail that had slipped by me initially did, however, emerge from the flow. In his last draft, Stan had replaced the epigraph to the final section with the last line from Palestinian-American poet Hala Alyan’s 2020 poem “Spoiler:” “I’m here to tell you whatever you build will be ruined, so make it beautiful.”

This would have to be enough.

[ad_2]

Source link