[ad_1]

Featured image: Decatur Street, New Orleans, 1850, by Gaston de Pontaba

The narrator in Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man is a Black man simply trying to live the American dream. His journey—through childhood, higher education, career, and activism—is one of disappointment. No matter what he does, he’ll never win. He rarely expresses any positive emotions like tenderness or joy. I understand the narrator’s anhedonia is an artistic choice. His failure to crack a smile is not a bug; it’s a feature. Invisible Man is about how racism is evil and saps opportunity from even the most intrepid among us.

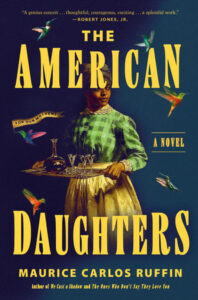

The main character of my new novel, The American Daughters, is a Black enslaved girl, Ady, who eventually becomes involved with a group of Black lady spies. Whereas books about enslaved people must on some level be about the cruelty of slavery, this isn’t the primary theme I was focused on. I know slavery was terrible. You, dear reader, probably agree. Instead, I’m writing about the power of community to sustain people in dark times. The novel is about kinship, friendship, and sisterhood.

This is a conscious choice on my part. I love my community and want to show it. Perhaps this artistic choice cuts against the grain. That doesn’t bother me.

Even in the worst of times, humans have a way of coming together to lighten the load and provide hope for a better future.

You see, often when authors write about the marginalization of Black people, isolation is the go-to choice. See Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird. Up through my 20s, this was a favored book of mine. But as I got older, it’s fallen in my estimation. I’ve wondered why the Black characters seemed unconnected to any community at all. Atticus Finch is a pillar of their small town. Scout is well known. Even Boo Radley has a reputation. But the Black characters’ venn diagrams are oddly constrained.

Calpurnia, Atticus Finch’s loyal housemaid, is so concerned with the health and safety of Scout that we scarcely hear anything about her own family. The white townspeople are vaguely aware of Calpurnia. They’re only aware of Tom Robinson, the accused at the center of the book, due to his infamy. Neither Calpurnia nor Tom seems to have people of their own.

In Gone with the Wind, Mammy and Prissy are so tied to Tara Plantation that they can’t imagine a life beyond the fields even after they’re liberated. The assumption is that they have no family or loved ones who might be somewhere else worrying about them, spouses, parents, or children sold down river like cattle.

I’m a Black man from a Black family from a majority Black hometown (New Orleans), and I have extended family in rural towns from Oklahoma through Georgia. None of the behavior of Calpurnia, Mammy, Prissy, or the like comports to the behavior of anyone I’ve known. In my large extended family and community there are ties that bind, ties that can’t be forsaken even in death.

We writers have a duty to make life difficult for our characters. Conflict and drama are the taproots of good storytelling. My Ady has a hard life in The American Daughters. But one thing she isn’t is alone. That’s because loneliness wouldn’t have made sense given the historic milieu, and it’s not the story I wanted to tell.

My hometown, New Orleans, was very different than most mid-nineteenth century cities below the Mason-Dixon line. Louisiana was full of isolated rural plantations. But in the big city things were different. Half of all Black people in the New Orleans of 1840 were free people of color. By setting the story in the city limits rather than in Lafayette or Franklin means that many of the women Ady encounters aren’t just free, they’re prosperous. And despite the efforts of the slave masters, these free and enslaved Black people were connected.

Sometimes families were mostly free, but some members were enslaved. Sometimes vice versa. Either way, everyone interacted with everyone else in the markets, on the streets, and in the businesses. Alliances were forged. A free person of color might buy freedom for their enslaved loved one. Still, many people never found freedom in the ante-bellum period.

To be clear, Ady, like her mother Sanite, is enslaved. Slavery is one of the worst institutions our species ever made because it is a socially enforced collective poverty. Ady and Sanite and the other enslaved characters don’t enjoy their social status. But they enjoy each other.

In stories where characters are in grave societal peril, I believe we shouldn’t lose sight of their humanity.

The man who owns Sanite and Ady is named du Marche. He has scenes with the mother and daughter, but his appearances are intentionally limited. He’s the least interesting character in the book to me. Sanite is interesting because she’s a good and loving mother from a mixed African and Native American background who knows carpentry, foraging, navigating waterways, self-defense, etc. Ady is interesting because she’s spirited, kind, brave, and loving. The women in the spy ring, the Daughters, all have special skills that aid them. And the Daughters collectively understand that they’re part of a continent-wide struggle for self-determination.

And as they plan their sabotages, they like to make finger sandwiches and tea with honey for each other.

Why? Because they’re friends, they’re family, they’re sisters. They’re each other’s “magnitude and bond,” to quote Gwendolyn Brooks. While much of the world discounts them, they laud one another, each is an oasis for the other. So whenever more than one of them are together there will be jokes, cajoling, lewd remarks, and delicious finger sandwiches.

My point is that even in the worst of times, humans have a way of coming together to lighten the load and provide hope for a better future. Ady has little reason to believe that she may one day find freedom. But at the very least, her mother and the other women in her life make sure Ady knows she is loved.

In stories where characters are in grave societal peril, I believe we shouldn’t lose sight of their humanity. Indeed, in the darkest of times sweetness and beauty have a way of flourishing. Stories are empathy generators. Far be it from me to flatten my characters and destroy the opportunity for connection. More than ever, now is the time to recognize the depth and grace of our marginalized communities.

__________________________________

The American Daughters by Maurice Carlos Ruffin is available from One World, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.

[ad_2]

Source link