[ad_1]

Islamophobia manifests in various forms depending on your background, your culture, you presentation, your race. The Islamophobia I’ve experienced has a flavor of anti-Arab prejudice, and growing up in America, I don’t remember a time before it. Still, I consider myself privileged on the discrimination spectrum.

Maybe it’s because growing up in Southern California, surrounded by Mexican restaurants and Asian markets and mosques, it was easy to forget where and who I was. It felt like there was no clear majority, and I believed that the attending weekly house parties, participating in extracurriculars at the masjid, and spending a third of every other year in Syria was the collective American experience.

But no matter where you are in America, visible Muslims get all the main character, dramatized experiences: cue the stranger yelling at my family in the parking lot to go back to where I came from, the isolation in those hideous middle school years, the shouting at me on the train, the impossible elbowing into narrow spaces built only for marginalized people.

These canon events were integral to the formation of my identity, but at their core, they are overdone, hyperbolized attacks that lack creativity. They’re reserved for filmmakers and writers who never spoke to a Muslim or Arab in their lives to depict the stereotypical experience. At this point, telling me my rice is over seasoned irritates me more than claiming that my faith poisons minds.

Unoriginal.

I’m used to being called a threat. We are told we are threats ever since we can walk, though our support systems and communities assure us that it’s false. They envelope us in a cocoon of safety, gifting us with space to be ourselves and we thrive there. Because threats don’t get an education or teach classes or treat patients. Threats like what we see on the news almost never look like us.

My novel is another window into our lives and another hand extended to others.

But then one day, someone in my university classroom said I spoke well, and it wasn’t a compliment. The next day, I spoke up less. Then she huffed about how I dressed too well with that rage in her eyes. I wore sweats the next time I came around. Then she claimed I walked too confidently, and that’s when I saw her comments for what they were. Because I’m a Muslim Arab woman who wears the hijab, and being myself without giving up an inch of my identity made her feel less. And rather than confront her prejudice, she decided to unleash her discomfort wrought on by her prejudice onto me.

Over time, I adapted to make myself smaller. I learned to make myself sound dumber. I convinced myself that the people I avoided or the activities I chose to participate in weren’t consequences of the microaggressions and macroaggressions, but rather a result of all the amazing experiences I could find elsewhere, I’d effectively cornered myself into my comfort zone. The discrimination is embedded into our lives like a germ, and we gaslight ourselves into thinking it’s the footnote or the ugliest part of the setting in a book. It’s in the background, we tell ourselves, it doesn’t define us. Because if we relegate it to the margins, it can never harm us.

It is a privilege and a delusion to refuse to allow the prejudice to dictate one’s life and sense of safety. Because the fact is that the anti-Palestinian, anti-Arab, Islamophobic rhetoric in America is to blame for the stabbing and killing of the Palestinian American six-year-old Wadea Al-Fayoume and the shooting of three young Palestinian men in Burlington, Vermont in the past few months alone.

The dehumanization of Arabs continues to be the narrative that allows the genocide in Gaza and the continuous attacks on Arab countries. It is the reason that deaths have become a tally rather than a script of stories of martyrs and their ended dreams.

My novel, Six Truths and a Lie is the story of what happens when the Islamophobia and anti-Arab prejudice ceases to exist as a part of the setting or a concept dissected in articles. Told in alternating perspectives, the six teenagers are falsely accused of an attack on a Los Angeles beach and must navigate questionable policing, trials, and their relationships with each other. Their various experiences with Islamophobia and prejudice shape their actions and alter their futures.

Writing this novel was a sort of reckoning, an acknowledgement of all that I had pushed aside to the margins. I learned about real life stories not too different than those of my characters like the Holy Land Foundation Five. In 2004, five Palestinian American fathers were convicted of “supporting terrorism” following a trial that was fraught with controversial procedures and tactics. We live in a world where five Palestinian American dads who donated and fundraised for a charity for Palestine become victims of injustice.

My inspiration for the novel from my life too, like the effects internalized hatred on one’s sense of identity. Or the effects of the Patriot Act: The questionable strangers who approached kids at the local masjid, the ominous click of the wiretap, or the extra hour at customs waiting for my little brother.

It’s unfortunate how relevant this book is right now. But I have hope, while prejudice is on the rise but so is the newfound empathy and community that Muslims and Arabs are discovering with other marginalized communities. Look no further than the rallying on social media to raise awareness and expose mainstream media’s dehumanization of Arabs and Palestinians. So many voices are speaking up in the face of egregious injustice. My novel is another window into our lives and another hand extended to others. May we speak up the veins in our necks bulge. May we walk confidently into rooms demanding to be heard.

__________________________________

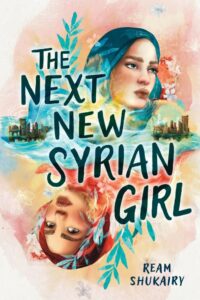

The Next New Syrian Girl by Ream Shukairy is available from Little, Brown Books for Young Readers, an imprint of Little, Brown, a division of Hachette Book Group.

[ad_2]

Source link