[ad_1]

The Watson Girl had only been missing a matter of minutes, yet she could feel the tension mounting, the disaster taking shape. Her cousins were calling her name loudly, angrily, like she should reveal herself, but there was no way she was going to do that. At home she’d given up on hide-and-seek. All the spots in her flat Tulsa house had long ago been scouted and discovered. Her mother had to pretend not to know where she was, and that wasn’t any fun, so the Watson Girl played other games.

But here, in Mankato, Minnesota, in a game that sprawled her aunt and uncle’s two-bedroom apartment, the mortuary below, and the lawn out front, hiding spots abounded. At first she’d hidden in the storage closet, knowing it was a terrible choice, not feeling particularly invested in winning. She flipped on the overhead light with a tug of its chain, scanning the shelves, mostly board games, photo albums, and old dusty trophies, a whole series of ancient Mankato High yearbooks. She did the math in her head, finding one that lined up with her mother’s high school years, 1985, and she flipped off the overhead light, stealing out into the hall, down the stairs to the mortuary, the yearbook pressed to her chest.

Wandering the showroom of coffins, she ran her hands along those shiny caskets with their silken insides, considered climbing in. No, that would be too obvious. She went to the window to get eyes on her cousins, but the only person she saw was a neighbor boy, about her age, riding circles on his bicycle. He seemed perfectly content in his circles, eyes off, a deep-thinking kind of look.

What she really wanted was some time alone, so she pushed past the door her uncle specifically said not to open, the only room in the whole place where she wasn’t supposed to go. It was obvious why, the dead woman lying on a table, her pores showing like caverns through unevenly applied foundation, her cheeks green despite the clownish pink blush. The girl gently poked the woman’s cheek. She tried to lift an eyelid, which didn’t come easily, until she saw why—a flesh-colored disc had been slipped under the lid, spiked and holding it in place. She pulled away, the eyelid half-raised to terrifying effect, the spiked disc poking out.

She climbed into the waiting coffin that she assumed belonged to the dead woman, who was not old in the way of a grandmother but middle-aged like the Watson Girl’s mother and very slender in her pale-blue skirt suit. The girl liked the color choice, the shade of sky, and it made her like the dead woman, and she told her so, “I like you,” before she closed the lid, marveling at the chill the white silken fabric pulled from her skin, holding that yearbook to her chest. She was alive, in a dead woman’s box, and she knew she shouldn’t be there, yet she didn’t get out. She did, however, reach down and remove her shoes, placing them on her thighs, so the ugly polka-dot dress her mother had forced her to wear would be the only thing they dirtied.

Her cousins, those giants, made their way into the showroom. They were teenage, the girl a senior and an absolute tower who played center on the high school’s basketball team and had many suitors. The boy was a year younger, a football player who liked to tickle the Watson Girl. She was twelve and had the arachnid legs of a child, and when he got on top of her, he’d make her laugh until a little pee escaped. He was handsome in a mean way and she was afraid of him. She could hear her cousins on the other side of the door, trying to decide what to do. They agreed to check the yard out front, and she heard them go, and she was glad.

She lifted the coffin’s lid and studied the yearbook. Embossed on its leather cover was the word Otaknam. Running her fingers over those letters, she wondered what it meant, Otaknam. She opened the book, scanning all those smiling teenage faces, serving the same looks dorks and losers have affected for eons, only with bigger hair, until she found her own face, third from bottom, second from left, drawing in a shocked breath.

She went elsewhere in her head, to Tulsa, her home. She saw her father grinning from the driver’s seat of his temperamental Audi as she bounded down the stone walkway, hopped in next to him, and they were off, to some place that offered a buffet where they would pile their plates with salad and baked potato and all manners of pasta, and Mom wasn’t there to make them finish. They would see movies and play mini-golf and swim in the pool at the apartment complex where he now lived, where he introduced her proudly to his neighbors and the security guy with a lean mustache who slipped her a butterscotch. Sometimes she’d find an earring under her father’s pillow or a woman’s tennis sock beneath the couch. She’d ask her father who they belonged to and he’d grin and say, “Oh, that must be your mom’s,” but her mother didn’t wear tennis socks, and that earring, a giant gold hoop—gauche, her mother would have called it. The girl had never seen it before.

She said to her father, “I’ll take it home then,” and closed her hand around it, and he smiled again, bribing her with ice cream and a movie, a promise that someday soon she’d stay overnight, if she’d just return the damn thing.

While he was on the phone in his bedroom, she scoured the apartment for clues, anything—she could feel it calling to her, a secret. In the junk drawer she found a key and kept it for herself.

*

Not me, the girl realized, staring at that yearbook photo, but her mother—awkwardly extended neck, rehearsed smile. The girl slammed the yearbook shut and closed the coffin. She could stay here longer. Avoid her cousins, her mother, who was stomping around the showroom now, calling, “It’s not funny, you’re scaring your aunt, your cousins, come out now!”

Her mother’s worries were already many, so it wouldn’t take long before she lost it, crying and angry. It was hot in the coffin by then, the fabric warmed to the temperature of the girl’s body. She adjusted, stretching a leg, finding new fabric to cool her.

On their weekly visits, her father liked to take the girl on drives around the ORU campus. He’d make fun of local hero and dead man Oral Roberts. “The guy used to go on TV and tell people if they didn’t donate, he’d die. I’m not kidding!” Her father would drive extra slow as they toured the campus, all gold-gilded and honking co-eds in convertible Rabbits. He always smiled at them as they passed, even the ones who gave him the finger.

“Look at those hands,” he’d say, stopping to admire the great bronze sculpture, fingers pressed in prayer, as if a giant had been buried underneath the earth, his hands all that showed. “The biggest bronze sculpture in the whole world, if you can believe it.”

Could she believe it? Her mother said he was a liar. Said maybe they could all do with a healthy dose of distance. And even if the girl didn’t want to believe it, didn’t want to believe a word her mother said, she felt it too. “Are you sick?” she asked her father.

“I don’t think so.”

She reached across the car’s inner island, put a palm to his forehead as he drove. “There’s something wrong with you,” she concluded.

Her father was born in Lebanon, the son of French missionaries. She liked to tell the other kids that he was from the holiest place on earth, where Jesus himself walked. This made them all stop and listen. The popular kids would get jealous, try to trip her up with questions: “Oh yeah? What’s the capital city?”

“Beirut,” she would answer, so ready.

“Well, well, well,” they’d say, “someone’s visited Wikipedia,” turning the others with their tone, not a big deal, not worth their time. They’d shift into side conversations, leaving the Watson Girl with her memories, which weren’t even her own and were terribly holey. Her father was eleven when he moved from Beirut to Tulsa, and he didn’t like to talk about it. So she told her own stories. She did research, starting with Wikipedia, sure, but she liked the local travel sites best, with their broken English and quaint web design, their photos of smiling tourists in front of the Roman ruins of Baalbec or Areopagus of the Elders, that ancient oak of the Druze sanctuary—a tree with a name! Through her research into the French presence in Lebanon, she learned the word occupation. Imperialism. Partition. These were not nice words. Her father was quick to dismiss it, any talk of politics, shifting topics to the cedar used to build Solomon’s Temple in Jerusalem. “In the Bible,” he said, and she chewed on that for a while.

*

Her mother was gone now, searching the apartment again or out on the street. The girl was amazed, really, that no one had come into this room. They’d all taken her uncle’s dictum at face value, as if the room had been removed from their mental map entirely. Was it a skill? Knowing the rules and breaking them anyway. She was good at that. Once she’d lied to her mother and said she’d joined the chess club, but really she took the bus downtown, going through a part of Tulsa her mother would describe as seedy, clusters of tents crowding the sidewalk. People live in there, the girl noted, as the bus headed toward the river, tents giving way to shops and apartment complexes, sidewalks cleared of trash.

Between buildings, she could see the bronze hands from the ORU campus praying toward the sky, and she hurried on, the clock ticking, her mother waiting.

As she pushed through the glass door, the security guy waved her over. She felt a bit like puking. “Good to see you again,” he said, reaching into his desk for a butterscotch, which he offered her.

She’d sucked on that butterscotch as she took the elevator to the seventh floor. Her father’s door was at the end of the hall, and quietly she inserted the key into the lock. She found that it fit and pressed the door open.

*

Silence, no one in the showroom, no one upstairs. The girl imagined a storyline: Would they call the police, mount a search, put her face on milk cartons? Would her father drive all the way up from Tulsa to find her? Her socked feet tingled with the thought of it. She thought about the hours it would take her father to drive up from Tulsa, about asphyxiation, and she lifted the coffin’s lid a few inches, feeling the cool flood of outside air, the new rush of chemicals. She couldn’t see the woman on the table, though she felt her all the same and decided not to look. Privacy, they could each have that, couldn’t they? She whispered into the air, “My father’s a liar.”

Her cousins were out front and she dared to pull the curtain aside far enough to see the neighbor boy from before, no bike this time, running, her cousins giving chase. They were faster and pushed him down, and when he hit the ground, his eyes found hers in the window. She did something uncharacteristic: she blew him a kiss—why’d she do that? Then she closed the curtain, the coffin’s lid. Even so, she could hear the beating her cousins were giving that boy, and she found herself offering a reflex prayer of protection, she was so afraid for him. At some point this had ceased to be a game, and when she came out she’d be held responsible. Running her fingers over the embossed letters of the yearbook, it hit her, Otaknam—Mankato backwards, duh. How had she not seen it? She closed her eyes, suddenly very tired.

Her father’s apartment had been perfectly quiet. The butterscotch tucked in her cheek, she went to the fridge and cracked a cola, wandering into his bedroom, sifting through his dresser, where she found an open box of condoms, stuffing them back into his drawer.

She lay down on his bed, balancing the cola on her stomach. Why had she come here? Because she could. Because she knew she’d be alone. There was nothing to find, no secret to unearth. He’d been unhappy, and he’d left.

For no reason she understood, she sat up and spat the butterscotch onto her father’s pillow. Then she flipped the pillow over and fluffed it out. She was fixing to go when she heard a woman humming and followed the sound to the bathroom, pressing her ear to the door.

Go, she told herself, but she couldn’t possibly—she had to know. She pushed the door open, she saw a woman in the tub, her face covered in a clumpy clay mask, the water gray, cucumbers over her eyes.

The woman smiled. Her breasts, her heat-inflamed skin, the flare of dark pubic hair between her legs—the girl saw the woman in parts, in quick blinking flashes, naked in her father’s tub.

“Are you just gonna stand there?” the woman said. To the girl, it felt like a taunt; she was most certainly not going to just stand there. She picked up the first thing she saw, a bar of soap, and threw it into the bathwater.

“Jesus!” the woman shouted as the girl ran.

*

The Watson Girl woke in the dark, panicked, pressing her hands to the coffin’s lid, remembering where she was. She could hear the police officer who’d come, not his words but the sound of his delivery, which even she, with little actual police interaction, recognized, most likely from television. She had to pee and was thirsty. But to come out now? They would all be furious with her. Was she afraid of their fury? She thought about it—what it would be like when her mother got her alone—and cringed. She would stay a little longer. She promised herself she wouldn’t wait too long, though, because even at her age she had the occasional accident. Her father had always been nice about it, unlike her mother who hated laundry and made the girl wear everything until it smelled. That was the one time she’d cried for missing him. She’d woken wet and shaking with a nightmare she couldn’t remember and, like always, tiptoed around her parents’ bed to her father’s side. Only when she saw his side made up did she remember he was gone. He wasn’t there to help the girl stretch new sheets onto her bed, to tell her what he always told her when she had an accident: that as a boy he’d wet the bed too.

She wanted to help him. She believed that lying was a sickness, the only treatment honesty. She thought if he told her his story that maybe he would get better, maybe he could find a way to cool her mother’s molten core. The closest he came was at a Taco Bueno, where the pair devoured Mucho Nachos in a plastic booth.

“What happened to your mother?” the girl dared to ask. She could tell he didn’t want to talk about it, his brow knitted, eyes on his office-smooth hands.

“She went back to Paris shortly after I was born. She wasn’t a true believer,” he said in a tone the girl had come to understand recently as sarcasm.

“Why didn’t you go with her?” It didn’t seem possible, a mother gone, a child left behind with the father.

“They agreed, my parents, that I’d be better off with him.” “Why?”

He took a deep guzzle from his extra-large cola and wiped his chin with a paper napkin and she could tell that was it; he was done telling stories. She looked at her father’s features, trying to find something foreign, unidentified, something he wasn’t telling her. He’d never mentioned her visit to his apartment, her encounter with the naked woman in his tub, and she never mentioned it either. He didn’t take her on drives of ORU anymore; he no longer promised that someday she would stay the night.

*

The Watson Girl couldn’t ignore the relentless feeling of having to pee. Thirst, sure, hunger, fine, but her bladder had stretched beyond its capacity, becoming a thing outside her control. She was about to hop out, find a bucket or sink, when she heard her mother’s voice from the showroom just beyond the door.

The girl lifted the coffin lid to hear better. Her mother was speaking through sobs; then she was quiet. She said in a low angry voice, “Not your fault?”

The girl closed the lid and urinated right there in the coffin, wonderfully warm until it was cold and there was the smell now, worse than the chemicals, filling up the air around her.

She knew that tone, that specific tenor of anger—only for him. Her mother hated him, her mother hated her father. It had become fact, a way of being, a whole existence, that hatred. The girl had grown afraid of her mother, whose hands were lightning fast when she was stoked. It didn’t take much, a roll of the eyes, the huff of a sigh, and crack. Her mother’s fury wasn’t new. In her father’s absence there was more space, more quiet, and when it got unbearable, all the extra space and quiet, her mother would fill it up with her rage until the girl would wish for silence again. She was starting to forget her mother’s laugh, the way her hair smelled, the electric feeling of lying side by side.

On the girl’s last night with her father, the one and only time she slept over, they’d decided to order in pizza, play video games. Her father had a Wii and he liked the Mario games, said they felt familiar, so she raced circles around the Mario Kart track and drank too much cola, her heart racing with the caffeine and corn syrup, and it wasn’t until he was tucking her into bed that she worked up the nerve to ask, “You said your father was a missionary, but what does that mean? What did he do in Lebanon?”

“He spread the faith.” “Did he do good?”

“He spread the faith,” he said again. “Don’t you believe?”

Not for some time, she wanted to tell him, but she wasn’t ready yet to say the words aloud. She raised her chin, not a nod exactly, but her father took this as a yes. He sighed. “I believed then too.”

“Why’d you stop?” “Because we fled.”

She saw it now, the picture of his life, a missionary’s son, with friends and classmates and people who depended on him. What is a mission if you abandon it? All those years, all that sacrifice, only to arrive in Tulsa where he wasn’t wanted—he’d told her it was so. Her grandfather had died before she was born, so she had no memories of him, nothing to contrast her father’s story. He sounded like a coward, but somehow she knew that wasn’t the whole of it, that somewhere beneath her father’s story was another one and below that another one still.

“Because,” he said, as he kissed her ear, “we should have gone home with her.”

“Your mother?”

“Yes.” He flipped out the light, commanded, as if by reflex, “Say your prayers.”

The girl didn’t want to feel hope, but it was there, her hope—he wouldn’t let this happen. He wouldn’t let her move so far away.

Never once had she asked him if the woman who’d fled to Paris was alive. In the dead woman’s coffin, she wondered if she had a living grandmother.

The girl let her mind drift, hunger carrying her off, to Mount Lebanon, cedars growing out of the rocks, branches stretching outward like arms. She’d read somewhere that if the climate continued to warm at the current rate, the cedars would be isolated into the tiniest of islands, at the highest of altitudes, until they’d have nowhere else to go except the heavens.

*

The girl could hear her uncle as he retrieved the gurney, wheeling it outside. There was a moment when she considered running, but her legs were numb from nonuse, and she was afraid, unsure of where to go, sort of floating in a blank space. It had taken hours to get there, to nowhere.

Just before the move, her mother had applied to have her legal name changed, the girl’s too. They would go back to the mother’s maiden name, stripping the girl of her father entirely. “Watson,” her mother had said, “it’s a common name but it’s got kind of a catchy sound, don’t you think? Watson?” She wanted a fresh start and it was obvious she needed it, yet the girl couldn’t stop herself from throwing a colossal fit. Her mother closed the windows, dragging the girl into the hall closet. She was tired of the girl’s fits. “Tired,” she said. “You can come out when you’re done.” But the girl didn’t come out, not for hours, not until her mother opened the door and told her, voice muffled by their winter coats but clear all the same, “I’m never going to be sorry, not for this.”

The Watson Girl knew her father wasn’t coming. He’d agreed to the name change, the move, all of it, telling her it was best for everyone—what a lie. She knew it was best for her mother, but her father too? She couldn’t believe it, that he’d be okay with letting her go, but he was—that part was true. She’d driven all those hours, those miles of flat highway, fields and fields of corn and colossal clouds like great ships cast on the sea. They said nothing the whole drive, and the girl got lost in her silence and her mother got lost in her own, and the girl had a feeling like forever stretching before her, limitless like those fields.

Her uncle came back in with the freshly dead body. She couldn’t see him, but she knew it was so. She listened as he examined the dead woman on the table. She could almost hear him adjusting the woman’s misplaced eyelid, see him turn to the closed coffin, which he, being a detail-oriented man, must’ve known he’d left open. She heard him take a few steps, stop, wrench the lid open with theatrical confidence, as if to say I knew you were there! He looked down at her, not at all amused, and she was aware suddenly that he didn’t like her, and she sprang from the coffin, her shoes, which had sat on her thighs unnoticed for some hours, falling to the floor, the Otaknam Yearbook too. She called for her mother, the lights too bright, the air cold.

*

The Watson Girl woke on the pullout, wedged up against her mother, who was snoring into her own armpit. It was six, the girl would guess, maybe earlier. She had a crick in her neck and felt zapped from all the crying. Her cousins would never let her forget, and now she’d have to live with them for a time. She cringed, imagining it.

She would tell herself another story, she decided, going to the window. The neighbor woman was in the garden. She had gloves on, a broad sun visor, a little foam pad for her knees, as she sprayed her plants with a plastic bottle. The Watson Girl decided that she liked her, the neighbor, whoever she was, the story in her mind finding its form. A second woman joined the neighbor now, wearing a robe that was too short, feet spilling out of too-tight slippers, silver hair in a loose braid. She crouched down next to the neighbor and took the spray bottle from her hands, resting it in the dirt. Then she pulled the neighbor into her arms. The neighbor’s eyes flicked up at the girl, whose instinct was to hide, but she stood her ground, and together they stared as if it were a game, each daring the other to blink first.

__________________________________

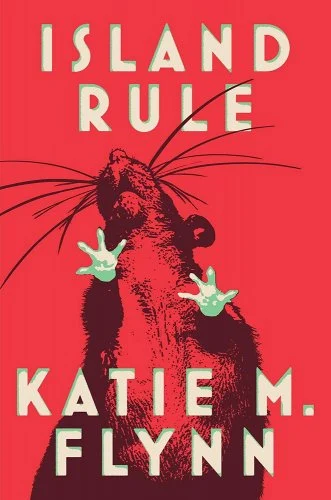

From Island Rule by Katie M. Flynn. A version of “OTAKNAM” has previously appeared in The Masters Review. © by Katie M. Flynn. Reprinted by permission of Scout Press, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, LLC.Used with permission of the publisher, Gallery/Scout Press. Copyright © 2024 by Katie M. Flynn.

[ad_2]

Source link