[ad_1]

A version of this first appeared in Lit Hub’s Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

1.

The metaverse is hot right now. Not only for Marvel (or Everything, Everywhere, All at Once), but in books, video games, even Facebook’s parent company, the metaverse is unironically omnipresent. I myself wrote a novel about the disappearance of a parallel-universe self, a premise I have felt as true to life since I was two and was adopted from Korea. The feeling that our reality has diverged from actual reality has become common.

It is a kind of melancholy, wherein the loss that we cannot move on from is our sense of what is normal. It is often prompted by an event like Donald Trump’s election as president, or, more recently, the coronavirus pandemic. At the height of the pandemic, that feeling was exacerbated by film and television, which depicted a world in which COVID never happened, so that we constantly encountered a version of our world that made it impossible to grieve it.

As pandemic restrictions faded, the loudest call, in America, was for a return to normal. As if the old normal was not already gone, a ghost haunting our present—just as climate change reflects carbon emissions from fifty years earlier, so that our current mess is the mess we made of the world in 1973. These things are not dissimilar, in that it is fundamentally too late to ever go back to normal. Normal is an assertion of agency over whatever we currently want to think of as strange. We can’t go back to normal because before the pandemic, normal didn’t mean putting vulnerable people at risk from an easily preventable disease. Or, of course it did: that disease was just racism, misogyny, homophobia, ableism, poverty, hunger, war, etc.

In fiction, norms are also assertions about what makes a story worth telling. My 2021 book Craft in the Real World starts from the premise that choices about identity like race and gender are always a part of writing fiction, since on the page, we decide what to include and what to omit. Lately, I have been thinking about our choices regarding global warming.

I titled a novel The Hundred-Year Flood without including in it any mention of global warming—which doesn’t mean that global warming isn’t there, just that it is an unintentional haunting. My metaverse novel is prefaced by a brief list of legal disappearances Asian Americans have suffered, from the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act to 1942’s Executive Order 9066, which sent Japanese Americans to concentration camps, all of which are tied to industrial imperialism and natural resources, though the connection isn’t explicitly stated. (For more context: the Chinese Exclusion Act followed the Gold Rush and the transcontinental railroad and reflected falling demand for Chinese labor, and Executive Order 9066 incarcerated only Japanese Americans on the West Coast, where many had found relative success on farmland whites had deemed unfarmable; the incarceration forced them to give up their property and businesses even while Japanese American laborers on fruit and sugar plantations in Hawaii weren’t relocated.)

Some scholars date the beginning of our current age, the Anthropocene, to the genocide of 50 million Indigenous people in the Americas in the 17th century, when global carbon levels stopped decreasing and started increasing (as measurable via traces in Arctic ice cores). My point is that our choices regarding identity are also choices about the climate.

In some of the best cli-fi, especially by BIPOC writers like Octavia Butler, that connection is apparent, and it has been argued that Black and Indigenous writers, especially, have used cli-fi to write about racial inequality. But I want to look at another, though related, aspect of the genre: the dominance within cli-fi of science fiction.

The term cli-fi purposely evokes this lineage. In a 2013 Guardian article that proclaimed its rise, cli-fi is defined as “novels setting out to warn readers of possible environmental nightmares to come,” which reminds me of a sentence from Donna Orange’s Climate Crisis, Psychoanalysis, and Radical Ethics: “When we cannot panic appropriately, we cannot take fittingly radical action.” But if warning readers to panic appropriately was a legitimate strategy in 2013, it didn’t work.

Part of our failure to panic may have to do with what scholar Timothy Morton calls “hyperobjects,” or objects so huge and massively distributed across time and space that they are impossible to point at directly. Elisa Gabbert explains further: “[The massiveness of climate change] paradoxically makes it harder to see, compared to something with defined edges. This is part of the reason we have failed to stop it or even slow it down. How do you fight something you can’t comprehend?”

Contemporary literary realism seems to prioritize the personal imagination and personal stakes over the collective imagination and collective stakes.

I can think of several norms we have in America for contemporary fiction that might get in the way of our ability to story (and therefore comprehend) hyperobjects, especially those that have to do with agency and the project of the individual, such as a character-driven plot (internal causation over external causation). It should be clear right away how a focus on the individual might make it difficult to handle massively distributed objects that no individual is personally responsible for yet whose consequences every individual must deal with.

Likewise, our emphasis on scene over summary, on showing over telling, on the concrete over the abstract, makes it hard to get at such a large scale of space and time. American fiction is often criticized abroad for its obsession with localized place and time (versus global place and time). The news sees an earthquake or flood as a story worth telling, but not global warming.

Contemporary literary realism seems to prioritize the personal imagination and personal stakes over the collective imagination and collective stakes, arguably more so than the Victorian picaresque or comedy of manners did. Think of the interplay between the personal and the collective in: “It is a truth universally acknowledged that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife,” from Pride and Prejudice. Perhaps as a result of the focus on personal imagination, American protagonists are always in the foreground (unlike, for instance, the protagonist in the Korean novel The Vegetarian, who is seen mostly through other characters’ perspectives).

Western antagonists even become antiheros of their own stories: the devil, the serial killer, the supervillain—a move that makes sense if you want to emphasize personal agency and conflict, both of which find their apotheosis in antagonists. That emphasis, however, also leads to a reliance on teleology (e.g. redemption arcs) and outcome-oriented stories of win, lose, or draw—change or failure to change—rather than stories of process and survival.

Lastly, an example that appears early in Craft in the Real World, there’s the way fiction writers are encouraged to defamiliarize, to embrace the uncanny and make the familiar strange. One of the most persistent dangers of norms and normalization (like how we have gotten used to the pandemic and to global warming, or giving up masking despite the threat this move poses to the most vulnerable) is the way our efforts to assert agency over the strange make what should seem strange seem unstrange. In other words, our problem isn’t always that we can’t comprehend global warming or other hyperobjects as objects; it’s that they have become so familiar to us that we don’t see them as objects at all.

I wonder why, then, we manage at least slightly better to panic appropriately and take appropriate radical action with hyperobjects like racism, sexism, and homophobia. The thing about storytelling and storytelling norms is that the more we hear a story, the more we are able to tell a story like it. In other words, we may be able to comprehend the story to be found in racism, for example, better than we are able to comprehend the story to be found in global warming, simply because we have consumed more stories about racism than about global warming.

On the other hand, I find this a dissatisfying answer. I actually think the answer has something to do with why cli-fi keeps turning toward the future rather than the present.

Cli-fi’s orientation toward the future would make sense if we thought that climate change, unlike racism, were still avoidable. The trouble is that it is not. The too-lateness, in fact, is why I started this essay. If cli-fi acts as warning, and it is too late for warnings, what is the point? There must be another way.

Some would argue this is a bad premise. Maybe the point of future-oriented climate fiction is not to warn us of the dangers of global warming, but to make us ask, as Min Hyoung Song does in Climate Lyricism: “What is possible now?”

There is no future point of no return, beyond which unchecked climate change will become catastrophic. That point has already passed. Conditions are already catastrophic. And the present is more and more dominated by the contours of this worsening catastrophe. What is possible now?

Sci-fi author Samuel R. Delany (who famously said sci-fi is not about the future) argued that what sci-fi does is present us with just such a range of possibilities. Delany claims that by showing us as many alternatives (“good and bad”) of what the world could be, sci-fi gives us control over our present choices—by which, I take it, he means the choice of what kind of future world we want to make.

Cli-fi’s orientation toward the future would make sense if we thought that climate change, unlike racism, were still avoidable. The trouble is that it is not. The too-lateness, in fact, is why I started this essay.

It’s easy to see sci-fi and cli-fi as useful exercises of the human imagination. And yet, ultimately, I worry that the real-world effect of solutions out of our control is a lot like the effect of an individual who does all of the little things that currently are within our control: the individual who stops eating meat, uses very little electricity and water, always recycles, takes public transportation, etc. In other words: statistically insignificant. Very few have the power to make big changes real, and probably even fewer of those people are reading cli-fi.

My concern is one of audience. What kinds of stories can we tell for readers who will face a world vastly transformed by climate change during their lifetimes and who have little agency over that world? How can a novel story a kind of being in the world (to borrow Milan Kundera’s definition of a novel, itself borrowed from Heidegger) that might help its readers survive climate change?

It seems to me that this kind of storytelling is what we do when we write fiction about characters surviving racism, sexism, and other systemic inequalities we face each day in regular life, when we write about the real-world problems our readers face. (I don’t mean real here as in naturalistic, but rather in the way Julio Cortázar says he writes realism: as a way of making reality realer.)

The trouble with depicting a way of surviving climate change is that we don’t actually know what surviving climate change looks like. We don’t know how people will be living only five years from now, which is a commonly given estimate of the time it takes to write and publish a novel. In addition, scholarship on how climate change affects people psychologically and emotionally (the stuff of novels) is much less established than the same kind of scholarship with regard to racism, sexism, homophobia, ableism, etc.

If not for climate change, I could roughly predict what kind of racism I will face for the rest of my life, because I have faced the same kind of racism for my entire life so far. What destabilizes that future survivance is precisely the climate. Current models predict that global warming will result in a global refugee crisis. That crisis has already started. Russia has invaded the Ukraine for oil. South Asians are being shot in the Mediterranean trying to get to Europe. It is easier to write about a future you can make up to the last detail than it is to write about a present you can’t describe. How do you imagine being in the world when the world is unimaginable?

2.

In the book Radical Hope, psychoanalyst Jonathan Lear writes about the “last great chief of the Crow nation,” Plenty Coups, who led his people through the transition from a war-oriented culture to life on the reservation, where intertribal warfare was forbidden and traditional Crow values therefore ceased to hold any meaning. In fact, the meaning of the name Plenty Coups relies on understanding the most valuable of all traditional Crow feats: those of planting a coup-stick and counting coups. On the reservation, these feats became impossible, but more than that, Lear suggests, they ceased to make sense as feats at all.

Lear claims he wrote Radical Hope out of interest in something Plenty Coups told the white man who recorded his stories of Crow life before the reservation. When the white man asked Plenty Coups to tell some stories about life after the reservation, Plenty Coups said that after the buffalo died out, “nothing happened.” He said the white man knew that part of his life as well as he himself did.

Lear wants to take this seriously, whether Plenty Coups was exaggerating or not. It’s quite a claim, Lear writes, to say that anyone else knows your life as well as you yourself do, especially someone outside of your community and culture. Lear hypothesizes that “nothing happened” after the buffalo died because nothing after that counted to Plenty Coups as a happening.

Throughout this breakdown of meaning, Plenty Coups was an exceptional leader. Despite multiple broken treaties—typical of the United States government—he managed to secure more of the Crow’s traditional land than most other tribes were able to safeguard of their territory. The Crow weathered the transition relatively well, and much of that success seems attributable to Plenty Coups.

What allowed Plenty Coups to anticipate the destruction of a traditional way of being was a dream: in the dream, the buffalo disappear and all the trees are knocked down in a storm (hello, global warming) except one. The one tree that survives is home to the Chickadee, a bird known by the Crow as a good listener who learns from the wisdom of others. The Crow elders interpreted this dream as predicting that their world would end and that, in order to survive that ending, the Crow would need to become “like the Chickadee.”

Notably, the dream indicates no particular way forward, only an openness to other ways of doing things. It’s impossible to predict from a dream what world is coming or even how the existing one will end. All the dream could tell the Crow was that there would be an end, and that they would have to find a way to survive it, notably a new way, a way they did not already know. They would have to adapt to whatever storm was coming without knowing what it was—and, crucially, without even having the concepts with which to describe it. This is what Lear calls radical hope.

The end of the Crow way of life is not analogous to moving to another country or learning to speak a new language—it is the end of anything that can be considered in Crow terms as a happening. Such a transition is an incredibly difficult thing to imagine, let alone face. It is the end of story. Plenty Coups can tell no story of life after the buffalo died that the white man cannot tell. The culture with which he understood what a story was has ended.

“The situation we are dealing with here,” Lear writes, “. . . is the breakdown of a culture’s sense of possibility itself.”

If there is no longer a way to understand what is possible, the possibilities offered by sci-fi or cli-fi—possibilities that Delany says are not about the future but about a dialogue with the present—will no longer help us.

In The Unreality of Memory, Elisa Gabbert notes that after Chernobyl, witnesses often expressed the very inability to express themselves: “I can’t find the words.” “Nobody ever described anything of the kind to me.” “Never seen anything like it in any book or movie.” One of the changes we might need to make in order to face our changing planet, Gabbert suggests, is “a shift in aesthetics.” New words, new concepts, new stories, maybe a new sense of what is beautiful and necessary and true. Or even, as has been suggested by other climate theorists, a new sense of what is subject and what is object.

An echo from Song’s Climate Lyricism: “The parameters of reason itself need to be tested and expanded, and dismantled if necessary, so as to make possible alternative ways of living.”

So far, climate fiction has done a lot of turning to the future to test and expand reason. I’m interested now in stories that dismantle it.

3.

In my last semester in Oklahoma, I taught a grad course I titled “The Craft of Making and Unmaking,” in which, alongside student work, we read four novels: A Children’s Bible, by Lydia Millet, Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead, by Olga Togarzcuk, The Disaster Tourist, by Yun Ko-eun, and Earthlings, by Sayaka Murata. Each of these novels establish a set of norms only to overthrow them. It is Earthlings that I will linger on here. [Spoilers ahead.]

Earthlings opens with a trip to a grandmother’s house in the countryside, where each year relatives gather. The title refers to the narrator’s (Natsuki) claim that her stuffed hedgehog is an alien. Her cousin, Yuu, also believes he is an alien (because his mother is always saying he is one). In this first visit, Natsuki and Yuu play marry and promise each other to survive “no matter what.”

Soon we see why: Yuu’s father is out of the picture and his mother is suicidal. Natsuki is sexually abused by her teacher; when she tries to tell her mother, her mother blames her.

On the next visit, Natsuki wants to lose her virginity to Yuu as soon as possible—so she won’t lose her body to her teacher first. While they are having sex, their relatives find them. Because of the scandal, the cousins are separated for the next 23 years.

When we come back to Natsuki, she’s 34. Now she too thinks she is an alien. In a flashback, we learn why. When she was still a child, Natsuki went to her teacher’s house in the middle of the night to kill what her alien hedgehog calls the “wicked witch.” In a kind of dream-state, Natsuki stabs a lump on the bed over and over again. Afterward, the hedgehog uses its final words to reveal that Natsuki also has alien origins.

As an adult, Natsuki has no interest in sex. She marries a hikikomuri, Tomoya, who is in complete agreement. Tomoya wants to escape society’s norms, so Natsuki is ideal, since she is an alien. Tomoya wants to be an alien too. Everyone in their family wants them to join what Natsuki, with her “alien eye” sees as the Baby Factory: they are supposed to have sex and reproduce.

To get away, they flee to the old house in the country, in which Yuu now lives alone. Yuu thinks he is a human now, but they try to convince him to be an alien again. Together, they live a kind of alien life: they stop showering, use almost no electricity, “forage” food from their neighbors, make all decisions together. But of course, this life cannot last.

I keep thinking about the ending of Earthlings and what the purpose of making and unmaking a story, a character, a world, might be—and I keep coming back to radical hope.

I hesitate to write this, and yet: here’s where it gets really weird. It turns out Natsuki’s sister knew about the murder all along. She’s been cheating on her husband, and when he finds out, she thinks Natsuki ratted her out. She tells the dead teacher’s parents that Natsuki is the killer. The parents show up at the house in the countryside, and in the struggle, the parents end up murdered.

Broke and starving, Natsuki, Tomoya, and Yuu decide to feast on one of the corpses. Afterward, they discuss whom to eat first if they run out of all food. In fairness, they decide to taste each other and eat the most delicious one. The novel includes an amazing description of their three-way consumption. In the morning, Natsuki’s family shows up. What they find, disgusts them: The three aliens are triumphant, glowing, and all of them, each of them, is pregnant.

It’s a stunner of an ending. For one, the book has led you to believe that being an alien isn’t real, only a metaphor or self-defense mechanism. Then there’s the peaceful, zero-emissions life the three outcasts have in the grandmother’s house, which is upended by true happiness once they have eaten each other and become pregnant. My class also discussed how the book describes our world as a Baby Factory, yet the three aliens end up blissfully with child. They face no repercussions for the murders they’ve committed, not to mention the cannibalism. They have no regrets.

Reading, it is impossible to imagine what has happened visually, how much of the aliens is eaten and how much remains, how much they are individuals and how much one being; you know only that whatever they look like, it makes the humans vomit. It is an ending that is completely baffling and completely triumphant—whether you like it or not, it’s something you probably will not forget.

I asked my class to think about why Murata would end her novel this way. We could imagine (and this is what Murata claims in interviews) that it came out of her subconscious and even surprised her—surprised even her—but an author always has a choice over what ultimately remains on the page and what does not. What is the effect she is going for?

A word that predictably came up a lot was: alienation. In the end, one student said, he felt alienated from the aliens. We agreed that, until the ending, we identified with the aliens, sympathized with them, even believed in their ideals (no carbon footprint!). But ultimately, solidarity is impossible. Of course, because they murder two earthlings, eat one, then eat each other and get pregnant from it.

If this alienation from the aliens is truly Murata’s intention—and like Lear, I’m interested in the possibility that it is true rather than whether it actually is—what would be the point of drawing in and then alienating your audience like that?

When I did my Ph.D., there was a professor in my program who was incredibly popular. Supposedly, other professors would audit his classes. He lectured for four hours straight, and it was riveting. My feet would sweat just from the work my brain did.

One point he kept coming back to in his lectures was the danger of adulation. He understood his popularity. He claimed that the real reason Plato banished the poets from his Republic is because they write too well. Poetry is too hard to refute. Plato even depicts his teacher and main character, Socrates, as someone who must be refuted. In most of the dialogues, Socrates is unpleasant. You shouldn’t want to be like him. After, he was killed for corrupting the youth. If you end up agreeing with someone, what is the point of refutation?

I keep thinking about the ending of Earthlings and what the purpose of making and unmaking a story, a character, a world, might be—and I keep coming back to radical hope. Lear calls it “a peculiar form of hopefulness . . . basically the hope for revival: for coming back to life in a form that is not yet intelligible.” And elsewhere: “a commitment . . . to a goodness in the world that transcends one’s current ability to grasp what it is.” These sentences could have been written about Earthlings.

What Plenty Coups faced at the end of meaningful happenings, and what perhaps we face now on the precipice of a change that is unfathomable and indescribable, is the need for a conceptual framework with which to story the breakdown of story. We need norms of unnorming. We need the alien eye.

Here is the whole Samuel Delany quote:

Science fiction is not “about the future.” Science fiction is in dialogue with the present. We SF [sic] writers often say that science fiction prepares people to think about the real future—but that’s because it relates to the real present in the particular way it does; and that relation is neither one of prediction nor one of prophecy. It is one of dialogic, contestatory, agonistic creativity. In science fiction the future is only a writerly convention that allows the SF writer to indulge in a significant distortion of the present that sets up a rich and complex dialogue with the reader’s here and now.

In other words, climate fiction set in the future presents us with possibilities we might use to know and contest the present reality. And yet, I confess my interest lies in the possibility of alienating readers from Delany’s dialogue, in making the experience of distortion the experience itself. I’m talking about climate fiction where what is possible is already distorted by racism and sexism and other structural inequalities, so distorted that only a present breakdown of reality might help prepare us to survive what it is currently impossible to story.

__________________________________________

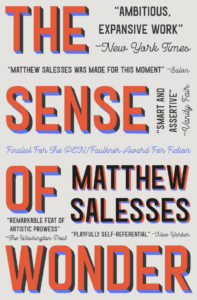

The Sense of Wonder by Matthew Salesses is available now via Little, Brown.

[ad_2]

Source link