[ad_1]

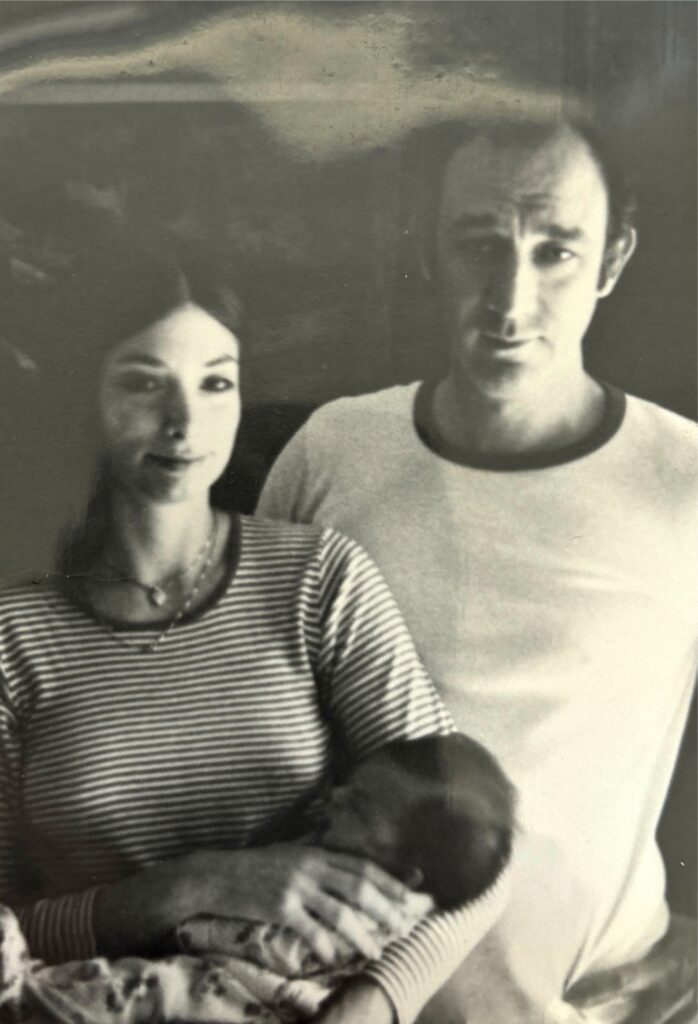

My mother came of age in Hollywood at the tail end of the 1950s, when girls wore white gloves to shop at Saks Fifth Avenue, when getting one’s ears pierced signaled a sexual taboo, when having sex before marriage was only for “bad girls,” and when a woman’s youth and beauty were considered her main assets, and in some cases, her only assets.

Luckily for my mother, she was beautiful, hailing from a long line of raven-haired Odessan women with impeccable skin and tiny waists. There are old black and white snapshots of my grandmother and her sisters-in-law huddled over champagne cocktails at The Coconut Grove, fox stoles hanging off their pale bare shoulders, their shining hair fashioned into rigid lacquered waves. My mother’s willowy aunts teetered on high heels in the backyard while my mom toddled after them in a starched white pinafore. They dieted voraciously. They wore dark red lipstick, clingy wrap dresses, a cigarette poised between their elegant fingers. They only cared about staying beautiful and young, at any cost, and often mocked my grandmother for not being thin enough.

As a teenager in the early sixties, my mom started modeling, the photographs revealing a gamine ingénue with heavy eyeliner and long limbs, wearing a geometrical shift, a cross between Audrey Hepburn and Twiggy. She doesn’t make eye contact with the camera but instead her gaze is demurely downcast, as if embarrassed by her obvious beauty.

She also worked as an extra for the studios, smoking and eating chocolate donuts while waiting all day for that sixty-second window when the camera panned the crowd in a dance scene or a beach scene, immortalizing her for a moment. Predatory producers flirted with her, as they did with all the girls, offering her parts for sex. Elvis asked her out, which just meant he’d drive you around the block in his Cadillac while you gave him a blow-job before he’d deliver you back to set. This was the age of Gidget, of the short busty blonde, chipper and extroverted, the opposite of my mom. Eventually she tired of being the stand-in, of the empty days waiting for a call-back, of never getting the role.

I remember my mother waking me up in the morning, a vision of false eyelashes as thick as furry caterpillars, her dark hair backlit by the sun splintering through the shutters. I remember knowing that I would never be as beautiful as she was. Stumbling out of bed, I stood before the mirror in tears because the plastic dog-shaped barrette wasn’t pinning back my hair properly. My mother tried to help but I jerked away. Exasperated, she huffed, “School isn’t a beauty contest!”

It’s not? I thought. At six years old, I already knew the score.

After my parents got divorced, my mom took me out to dinner a lot because she hated to cook. Men would send over drinks, their numbers scribbled on a napkin with notes like: Where have you been all my life? She basked in the male gaze, while I, an awkward fourteen-year old, played the sidekick, the kill joy daughter, the ultimate cockblocker.

How to stay beautiful, young, and thin were the three main topics of conversation between my mom and her friends. She weighed herself at least five times a day, recounting her caloric intake, before comparing it to how much I had eaten. She commented that when she was my age, she weighed less, always placing me five pounds heavier than she had been. Her best days were when she was asked for her ID at the grocery store and when people mistook us for sisters. She would often whisper, “Do I look younger than she does? How old do you think she is?” gesturing to some woman across the room. I always reassured her that she looked younger.

My mom and her best friend would compare chins, necks, age spots, frown-lines, cellulite. They played a game that involved pinching the top of their hands and timing how fast the skin snapped back into place. The longer it took, the older you were. They would endlessly discuss getting another facelift and then afterward, compare facelifts. Once, I interrupted them, announcing that I would never go under the knife. They erupted into hysterics, chiding: “You’ll be the only one hobbling around here, decrepit. You’ll do it. Just wait and see.”

A few years later, I drove my mom home after one of her surgeries, her face entirely covered by white bandages. As I gripped the steering wheel, she implored, “Why did I do this? Why?” Concentrating on the road, unable to look at the distressed mummy in the passenger seat, I could only shake my head.

In high school, I energetically attended a women’s studies class, led by a revered second-wave feminist but I feared I didn’t look like a serious enough feminist to the teacher because I wore pinky shimmery lipstick and denim miniskirts and desperately wanted boys to notice me. I purposefully dressed down on the days I had her class, stuffing lipstick into my front jean pocket, and wore an oversized flannel shirt, pretending not care about my appearance even though I did. We discussed The Beauty Myth, but it didn’t seem like a myth to me. Everyone wanted to be beautiful.

It’s painfully clear that my inherited ideas about how to be a woman are extreme and problematic.

By the time I was forty, I ended up going to a plastic surgeon, just for Botox, just a little bit. I couldn’t resist the desire to look young, or at least, younger than the mirror’s reflection, a diluted sad version of myself. The surgeon, a soft-spoken Italian, examined my forehead. I asked him how he got into plastic surgery. He said, gently injecting the toxin into the groves, “I like to fix broken things.”

Now that I have a thirteen-year old daughter venturing into womanhood, it’s painfully clear that my inherited ideas about how to be a woman are extreme and problematic, but at the same time, I knowingly subscribe to many of them. I weigh myself every day. I want to conquer time, to retain this fleeting thing called youth, while knowing it’s a futile quest. But, unlike my mother, I don’t want to get married five times. And I don’t want to be ruled by these unrealistic expectations to the degree that she was. I don’t want to die thinking about such ephemeral pursuits, or spend too much time in the present thinking about them either, and yet, it’s embedded in me.

What will I pass onto my daughter? Not the nights going to bed hungry, the years of counting calories obsessively, or the feeling of never being pretty enough, thin enough, good enough. And yet, how can I pretend that these prevailing norms, these stories we’ve constructed about beauty and desirability, are not powerful? I can’t. And so I’ll tell her my story, making sure she understands it’s only one story, one way, one version, and that there are multiple stories to choose from, with multiple ways to live them, as opposed to some ultimate, calcified truth about the female experience.

I hope that she doesn’t fall under that old story’s spell, cast over my grandmother, my mother, and me, a story that social media presents as shiny and improved but really isn’t. I hope that, one day, once she emerges from the morass of adolescence, she’ll read my novel about a mother and a daughter who challenge the stories we tell about ourselves, as well as the stories our mothers, grandmothers, and the culture have told us about how to be in the world. I hope she’ll decide how to live her own story, on her terms, keeping the parts that are helpful and wise, and shedding the rest.

__________________________________

The Mother of All Things by Alexis Landau is available from Pantheon Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.

[ad_2]

Source link