The medical industry is riddled with regulation and red tape. It breaks down into a medical benefit vs. pharmacy benefit, each with its own nuisances that make the medical industry complex feel like a scary corn maze during a bad dream. Interestingly, Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) were originally founded in the 1960s by pharmacists as a way to help insurance companies manage drug spending, negotiate prescription drug spending, manage a formulary (a list of drugs covered by the plan without prior authorization required), and lastly to establish a list of “in-network” pharmacies.

What was intended to streamline the pharma industry and help save costs has now caused an explosion and ballooning of costs to the American people. Three particular PBMs, CVS Caremark, ESI, and Optum, now dominate about 89 percent of the U.S. market. While three does not equal a monopoly, it sure does create a mafia. The main creation of these three PBMs arose from the responsibility to cover the cost of prescription drugs. Before insurance, the end payor was the patient. With these PBMs, they negotiate the prices they are willing to pay and hold the leverage in doing so.

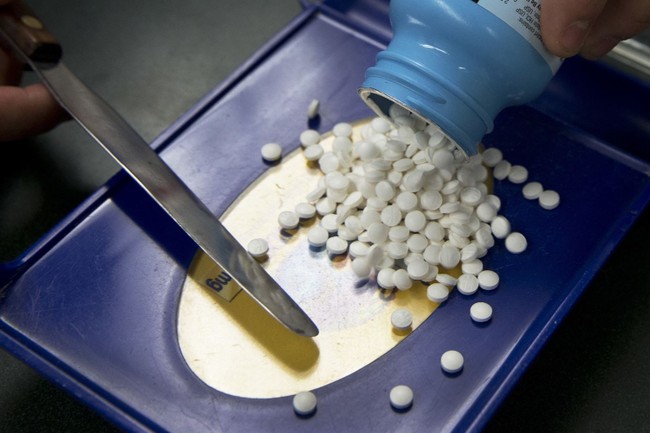

These back alley negotiations are very complex and conflate any form of transparency. One example would be the hot drugs currently, the GLP-1 analogs. A PBM can go to the makers of Ozempic and its rival Mounjaro and state, “OK, for each drug we allow to be processed, we want a rebate.” The drug manufacturer who is willing to offer the best rebate will be allowed on the formulary. One way this increases costs to the consumer is that PBMs will often prefer brand name (i.e., more expensive) drugs as a higher tier vs. generics, which traditionally cost pennies. This is due to the rebates that brand-name drugs carry vs. the cheap generics.

As a patient in the complex pharma industry, the biggest advocate must be the patient. Most PBMs will cover the full cost for what is called “preventive medicine.” A flu shot, pneumonia shot, COVID shot — all of this is considered “preventing” further costs down the line if you acquire the disease, namely the tens of thousands of hospital costs should the disease inflict major harm. As an independent pharmacist, I see the “prior authorization” game played out daily on both necessary and unnecessary medications. Let’s use the GLP-1 drugs once again. Most plans do not cover the indication “obesity” or “overweight.”

PBMs and insurers only cover indications that the drugs were intended for in their clinical trials, namely diabetes in this case. Most obese patients are on their way to a diabetes diagnosis, yet the plans make it difficult to obtain. Rather than dealing with long-term complications of obesity before they develop, such as microvascular (neuropathy of the arms, fingers, eyes, and or kidney failure) or macrovascular (possible stroke, heart attack), the plans will pay for drugs for these issues separately vs. the eventual more serious issues that can occur down the line. Requiring prior authorizations and prohibiting patients from critical life-saving medications puts a strain on the pharmacies that are required to assist the patients, and especially the patients who don’t get access to the medications required for the illnesses.

Lastly, what is the strain on the pharmacies themselves? I’ve previously written about this topic here. The Biden administration proposed to address some of the fees these PBMs take at the point of sale vs. after the fact in an attempt to allow for clarity. However, the strain this action caused has actually allowed one-third of pharmacies across our nation to close their doors and has been considered a disaster.

An Insider’s Perspective on Pharmacy Benefit Managers

Pharmacy Guild, Like Dock Workers Union, Cares More About Control Than Compassion

During the Biden administration, they did negotiate for direct price drops on 10 drug classes, which will take effect in 2026. Some have happened early, such as insulin costs dropping, which has been crucial for those who are insulin-dependent, while some of these have benefits, such as Eliquis, which millions of Americans take, a drug on the list like Entresto will go generic in July of 2025, rendering the brand useless as plans will allow for payment for the cheaper generic. While these ten drugs were met with much fanfare and publicity from the White House, the overwhelming consensus is that the true impact of this legislation will not significantly reduce the rising costs of healthcare.

Come January 20th, it’ll be interesting to see if the Trump administration can tackle this industry, which has Washington’s arms embracing it.

Michel Albert Daher, Pharm. D, APh, is a community pharmacist who has owned and operated three pharmacies located in California and Oregon. He currently owns one in the Los Angeles Area, which specializes in Oncology and long-term care services. He graduated from the Oregon State University/Oregon Health and Sciences University College of Pharmacy in 2013. He completed a one-year residency in ambulatory care at the Old Town Clinic located in Portland, Oregon, where he operated a pharmacy-managed diabetes clinic, which encompassed additional treatment for hypertension, hyperlipidemia, vaccine administration, and heart failure. He is currently an adjunct faculty in the division of pharmacy practice at Marshall B Ketchum University located in Fullerton, Ca. He also holds the title of advanced practice pharmacist, which allows him to prescribe or hold medications and order and interpret lab results.