J.C. Gabel: Most people know you as a novelist, short story writer, and poet, but you’ve been a painter almost as long as you have been a writer, correct?

Article continues below

Percival Everett: I’ve actually painted longer than I’ve written. I never thought of it as a career ever, but the way that I expressed myself, creatively—at least initially—was by painting. I started out late, in my teens. I just needed to do it. I always loved abstract work. I studied science and logic in school, so I wanted something that wasn’t inside my head.

JCG: Are the processes of writing and painting different for you?

PE: The relationship I have with painting is so different from writing, which is based on representational units in picking words; they attach to something in the world. There is a concept, and we know what these words, assembled on a page, are supposed to mean, and what they represent. They are amorphic, but they don’t exist without a context and reference.

People see what they need to see in order for the paintings to make sense.

And the paintings, on the other hand, it’s harder for me to talk about them because I’m working off an idea or feeling that is not based in words. There is a physicality to it.

But both inform the same need to make some sense of the world. In that sense, they are similar pursuits.

JCG: Your first solo exhibition, Once Seen, dealt with lynching, the same theme as The Trees, your novel at the time. Was that the first time that your writing and artwork intersected?

PE: The last show about the lynching was the only time in my career where the subject matter dovetailed in any way or were related.

This new show is about storytelling. But it’s not about anything I’ve written. The work is set up so that the viewer completes the picture. There are things hidden in these paintings and under these paintings, and some of the picture is not available. But people see what they need to see in order for the paintings to make sense.

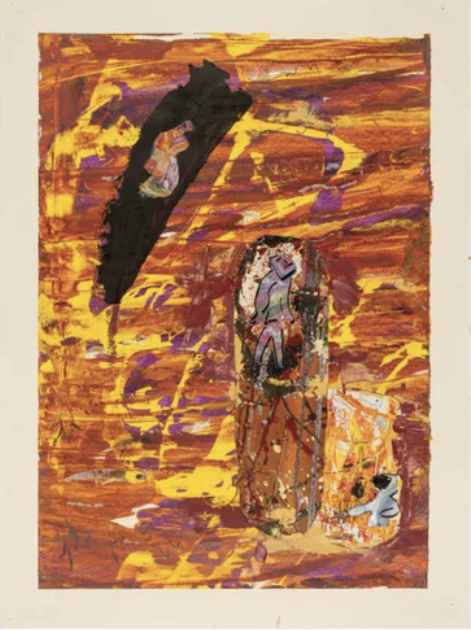

“Redaction No. 18,” 2024. Mixed media, collage on archival paper, 45 x 32.5 in.

JCG: These new paintings have a mixed media/collage technique. I can see now what you are saying about having to peel away things to see meaning.

PE: Collage isn’t new to me, but there is a different technique with these new paintings. The collage part is obscuring part of the picture you’re seeing. It’s present, but it’s not available, and that is what I meant by redaction. I don’t want it to be available; in part because I’m interested in how we make stories.

It’s like in a novel: You don’t know what happens to all the characters in the beginning of the novel. They exist someplace. You fill in those details as the reader goes along. If I as a writer imagine it, it doesn’t exist unless I fill in the blanks on the page to tell that part of the story. That is what I mean when I talk about redaction and that that idea is related to this new work.

Likewise, for me to expect you (or others) to see beyond what is present on a canvas, there must be something present that is not available.

JCG: Does either medium come to you easier?

PE: They come differently. Starting either one is difficult. But finishing the paintings is so much shorter of a process. But I think starting them is equally difficult.

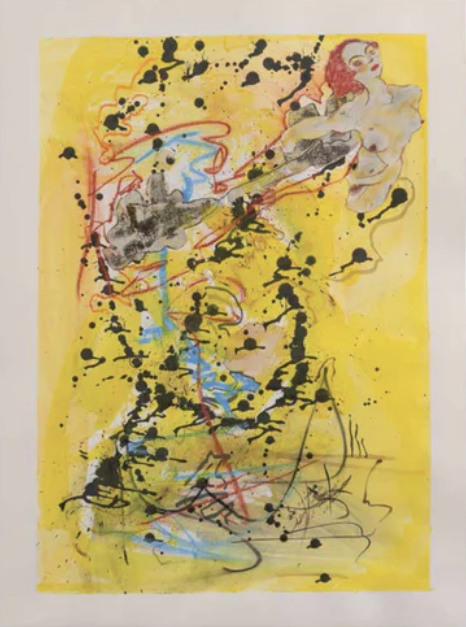

“Redaction No. 17,” 2024. Mixed media, collage on archival paper, 42.5 x 28.5 in.

“Redaction No. 17,” 2024. Mixed media, collage on archival paper, 42.5 x 28.5 in.

JCG: How much time do you typically spend on a painting?

PE: It varies widely—from a few days to the longest one, which has taken two years. And it’s not stopping and coming back to it a year later. I don’t count the ones I take four months off and then come back to them.

JCG: Another creative interest of yours is repairing and tinkering with guitars and banjos. How did you get started on that hobby and does it relate at all to your writing or painting?

PE: I’ve seen real luthiers at work. I like having a guitar that plays and enjoy working with the wood. At some point, down the road, I may try to step it up and make it more of an art practice, but for now, it’s just me tinkering and playing to unwind.

JCG: You are a musician as well, I should note, so it’s not unusual for you to be playing guitar.

PE: I played jazz guitar in various bands when they needed a guitarist to help pay for college when I was young. This was in Miami. Lately, I just like the blues and old-timey country music.

JCG: Can you talk about your writing and painting processes? I remember you telling me once that you do every first draft of a book on legal pads, handwriting them, and then you type things up and revise as you go. Are your paintings first done as pencil sketches?

For me to expect you…to see beyond what is present on a canvas, there must be something present that is not available.

PE: I handwrite out my first drafts of every book and then, later on, I put it all into a computer. Then I have a manuscript, and I go back and rewrite everything, sometimes several times over.With the paintings, it’s different. I would like to think that I’m planning them out, but as you know, a map is just an excuse to get lost. It can be difficult to know the beginning and end sometimes. It can get muddy and then I can’t fix it. I have to stop before that happens. Other painters may be better with this process. There is usually one point with painting where I think: I need to fix this or that, and then I stop myself and say, No. I like that it bothers me—that is when I know it’s done. I leave that spot alone.

“Redaction No. 2,” 2024. Mixed media, collage on archival paper, 31.5 x 23.25 in.

“Redaction No. 2,” 2024. Mixed media, collage on archival paper, 31.5 x 23.25 in.

JCG: Was there a flip of the switch with your creative pursuits as a young person, which then consisted of playing music and painting, when you began to write more seriously?

PE: I never thought about it. I got paid to play music to help pay for school, but I never considered myself a professional musician, nor did I aspire to be one. I was a confident guitarist. And in places like Miami, where I lived then, or Los Angeles, where I live now, I can’t go outside and throw a stick without hitting a great guitarist.

With painting, I also never really thought I’d do art as a career. I was studying philosophy and I realized I didn’t like it, at least as a profession. I’d always been a reader. Eventually, I just started writing fiction.

JCG: Let’s go back to jazz music and paintings and in particular, abstract paintings of the mid-20th century—the Abstract Expressionist period. There are some incredible jazz album covers featuring paintings that perfectly encapsulate the music on those records. Was that period of Bebop, Hard Bop and into the Free period—was any of that music influential on your work as a painter?

PE: Yes. The whole idea of a painting having boundaries—that is what jazz does. You have your melody. You can get far away from it, but you can’t lose the concept. Anything you want to do within those boundaries, and you can expand those boundaries more so with the music than you can, in a way, with the work on a canvas. The painting is within the frame. You can’t go beyond it traditionally. But in fact, you can expand beyond it using different techniques of layering, meta-painting. I’ve done that with some of these new paintings.

The abstraction can also turn itself inward so that you address the infinity, and you can never reach the middle. Just like jazz—when you listen to someone like Sonny Stitt—you might think these are long, fast runs but you then realize that they are all spinning around one thing—there is something connecting it all.

__________________________________

Redaction by Percival Everett is available from Hat & Beard Press.