Our quadrennial political party conventions can be entertaining to watch, a sense that history is happening right in front of you. Like Monday night. Key word here can be entertaining.

I’ve only been inside seven of them, each in a different role – go-fer, reporter, governor’s aide, press secretary, blogger, official delegate.

Each was a unique experience that helped assuage an abiding curiosity that emerged sitting on a living-room couch with my parents. If they were interested, there had to be something there.

With age comes an eye-opening realization that an abiding adult interest in a variety of things – classical music, college football, aviation, for instance – actually originated from early exposure to them arranged by my parents.

A prime example was that party convention almost exactly 72 years ago, much like the Republican one we’re witnessing this week in Milwaukee. Though my first was in grainy black-and-white.

My father was an engineer, an immigrant who grasped at a variety of experiences as he figured out his new homeland. He often took me along.

One week in mid-July 1952 I found him each evening planted in front of our 12-inch black-and-white DuMont television set. “Here,” he said, “Sit down.”

That was the very first time any American could witness their political parties in action, thanks to live TV.

The new technology and equipment was so immense and cumbersome that both parties agreed to hold their national convention in the same place, Chicago’s International Amphitheatre.

Little did I know that one day many years later in a profession I’d never heard of back then, I would be working inside that same cavernous structure as a journalist.

And then many years after that, attending numerous nominating conventions in cities across the country as I accumulated experience and history.

I remember two things from those 1952 weekday evenings: My parents’ rapt attention when Gen. Dwight Eisenhower spoke and the roll call of states to nominate him.

My father challenged me to name the next state up in alphabetical order. There were a lot more ‘M’ states than I realized.

For the summer of 1964, I was a reporter for a Memphis newspaper. I dodged evening assignments one week and blew an exorbitant chunk of my $75 weekly salary to rent a TV and watch the Republican conservatives and liberals duke it out in San Francisco and later the Democrats in Atlantic City.

I remember Lyndon Johnson floated several trial balloons for his vice-presidential partner, but Robert Kennedy was never one because of personal antipathy.

Four years later, I was an aspiring reporter on the New York Times when a journalism icon, Harrison Salisbury, the national editor, tapped me as his assistant for the Democrat convention in Chicago in that famous International Amphitheater I’d seen on TV 16 years before.

That arena was right by the mammoth Chicago Stockyards. And their bovine aroma dominated the entire neighborhood.

One of my daily tasks was to set up typewriters and supplies on the press platform for all our writers not 20 feet from the podium. I was also dispatched to buy Prince Albert pipe tobacco for James Reston, who would be my direct boss four years later.

It felt pretty big-time standing there beneath the lights where, 16 years before, I’d watched Eisenhower address the country while I sat on our living room couch.

Famous pols and journalists came and went all evening.

That was an angry, divisive time in America and its politics, mainly over the Vietnam War. Lyndon Johnson was forced to abandon his reelection.

Thousands of angry protesters roamed the streets destroying property and clashing with equally angry Chicago police, who had large horses and teargas. That stuff stings.

I was standing nearby at that famous moment when Sen. Abraham Ribicoff denounced the city’s Nazi police tactics and from the front-row, a furious, red-faced Mayor Richard Daley yelled and made a throat-slitting motion at his fellow Democrat.

If I’d had more experience by then, I might have predicted Hubert Humphrey’s defeat to Richard Nixon about nine weeks later.

Next afternoon, as I set up typewriters in the empty arena, I noticed maybe 200 people way up in the nose-bleed seats chanting support for Chicago’s mayor.

I reported this to Mr. Salisbury. In a flash he took off his All-Access pass, put it around my neck. “Go for it,” he said.

The crowd was led by a Democrat precinct captain who’d been ordered to take party workers to support the mayor. I talked to several about their Daley devotion and returned to our workroom, prepared to type up notes for a real reporter.

“No,” said Mr. Salisbury, “you write it up. Give me 500 words.”

And that’s how I wrote the first of some 5,000 stories in the New York Times over the next 26 years.

Although I was often writing about politics, my next party convention was a long time coming. In 1996, I was executive assistant for a governor speaking at the GOP convention in San Diego.

That involved scheduling media interviews, clearing his remarks through the stage controller behind the curtain, and coordinating with allied governors.

It was also there that I learned to watch where you’re going. I had just bought a hot dog, turned without looking to find a seat, and was punched in the gut by one of several stern men walking briskly by.

Bent over, gasping for breath, I looked up to see Jack Kemp, the new vice-presidential nominee, being escorted somewhere by a Secret Service posse, who thought I was making a move on their charge. Twelve years later I was writing Kemp’s obituary online.

I was at the 2000 GOP Convention in Philadelphia, often inside one of those Secret Service cocoons as press secretary for Laura Bush. She was about to become First Lady.

That was more pressure. During the preceding primary campaign, I would leave an hour-long event with her, turn my cell back on, and have 36 new messages.

Those were fascinating but tiring times that started with a 6 a.m. media appearance for her and ended near midnight after a long flight to preposition for the next day. But I learned so much about politics, the routines and practices, the dedicated people in it, some of whom I could do without.

I was especially fascinated by the advance teams. To my eyes, they are political magicians who blow into a city and in two days set up a major event in a nice bannered place that will appear packed on TV.

Some of them had worked for President Bush I and shared lessons, like renting media risers several inches taller than usual which allowed cameras to see over waving supporters with signs, keeping their candidate in sight at all times.

By 2008, I was back in journalism writing a conservative blog for the LA Times. I arrived, window open, at the security checkpoint for the GOP convention in St. Paul’s Xcel Energy Center. And was immediately greeted very close face-to face by the hot breath of the largest dog I had ever seen.

The soldier said, “Please exit the vehicle, sir.”

“Sure,” I said, “Is it okay with him?”

“It’s her, sir.”

I did blog posts and some TV hits for the Times’ TV station. Interviewed Jon Voight and Karl Rove. But the highlight for me was watching Sarah Palin in action, not the one crucified by media and undercut by John McCain’s own staff.

Until Palin, no one could defeat the vaunted political machine of Frank Murkowski to become Alaska’s governor.

I wanted to see the woman who did that. She was one of the most open, approachable politicians I’ve experienced. Friendly, a good listener, willing to chat with everyone at an event. And stay long after for selfies and autographs.

But her VP acceptance speech topped it all. It was basically her national debut. The pressure was immense. I was friends with her speechwriter, who told me of her relentless preparation.

She went over the speech countless times, tweaking words, reciting lines to make them smooth. She knew it very well.

Good thing because just as she started to speak to millions of curious viewers, the teleprompter broke. It started feeding her lines she had already said. So, she’s struggling to remember new lines several paragraphs ahead while past lines assault her eyes.

I’ve watched her speech several times like it’s a painting or statue. Maybe it’s me, but learning the components of politics over many years, the ability to communicate clearly despite any and all distractions, impressed the hell out of me.

Watching our current president try that, you can see the opposite.

Eventually, after perhaps 10 minutes, the teleprompter caught up to Palin. But my eyes couldn’t and still can’t detect the mechanical challenge. See for yourself.

I found the Democrat convention of 2012 in Charlotte to be the least interesting. Free of this year’s uncertainty and turmoil, it renominated Barack Obama and Joe Biden.

Perhaps my impression of a desultory gathering was colored by the first term’s awful events, the Benghazi murders, Solyndra and the IRS scandals, ObamaCare, and nearly $900 billion wasted on an ineffective economic stimulus program that despite Biden’s boast, was not at all “shovel-ready.”

I did, however, get a good selection of campaign buttons for my collection. My oldest is a William McKinley button from 1896. I was not at that convention in St. Louis.

However, I was in St. Louis for the 1972 People’s Party nomination of anti-war activist Dr. Benjamin Spock. The big news there was a walkout by the bored children’s caucus. Seriously. The famous baby doctor sent out for a large batch of comic books to buy their attendance.

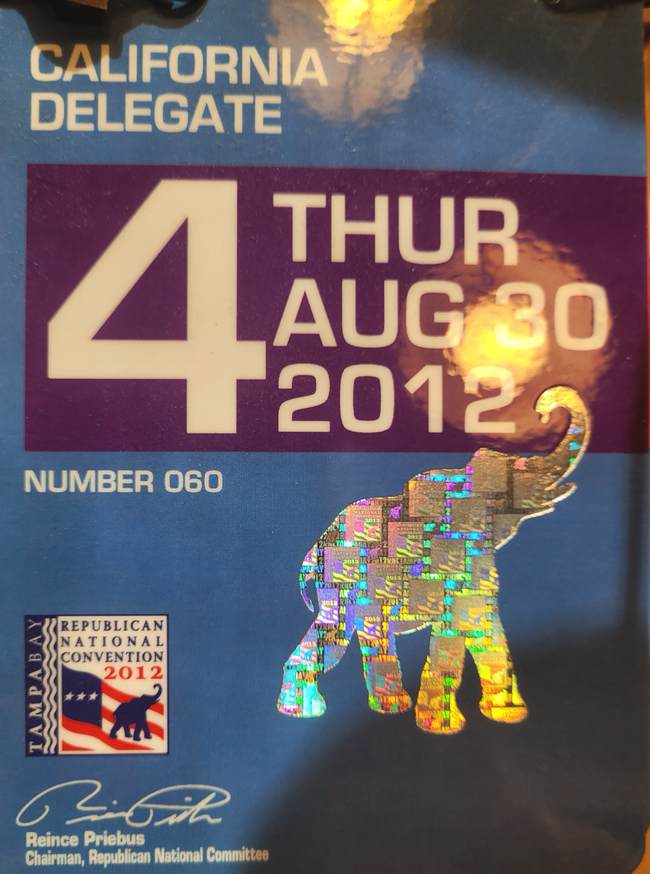

To round out my convention experiences and find out what it was like on the convention floor, in 2012 I applied to be an official Republican delegate, one of 2,286 total and three from my California congressional district.

And I made it!

It’s good to be king. And the same goes for Official Delegate. Most recent nominations are done deals, like mine in 2012. Conventions are to gin up base enthusiasm. The gatherings have long periods of blather when Becky Everywoman and Joe Workingclass get five minutes of speaking time and TV fame.

None of that was customary before television. That medium has turned conventions, like football games, into a TV show to market something, in this case the party’s brand and replace the old gritty nominating process.

In 1924, for instance, it took Democrats 15 days and 103 ballots to nominate John Davis. He went on to lose easily to incumbent Republican Calvin Coolidge.

The Tampa delegate badge let me follow my curiosity almost anywhere in the building. I wandered all over the place, talking to people, asking how things worked. And, of course, acquiring more buttons.

To be honest, those delegates and the ones you see on the floor this week don’t really have much to do. Which is fair because everyone pays their own way for the experience.

Delegates have become mostly cheering/applauding props for the show going out across the country. There’s much mingling on the floor, chatting even during the numerous lesser speeches, which can drone on. And much excitement when Clint Eastwood showed up.

At the end of one woman’s long speech in St. Paul, I hustled with many others to the men’s room.

No one really looks at each other standing at the urinals. The man next to me sighed with relief and said, “Geez, I thought she’d never stop talking.”

That time I did look over. It was Sen. Alan Simpson of Wyoming.

This is the 19th in an ongoing series of personal Memories. Please hare yours in the Comments. Links to the others are below:

As the RMS Titanic Sank, a Father Told His Little Boy, ‘See You Later.’ But Then…

Things My Father Said: ‘Here It’s Not Loaded’

The Terrifyingly Wonderful Day I Drove an Indy Car

When I Went on Henry Kissinger’s Honeymoon

When Grandma Arrived for That Holiday Visit

Practicing Journalism the Old-Fashioned Way

When Hal Holbrook Took a Day to Tutor a Teen on Art

The Night I Met Saturn That Changed My Life

High School Was Hard for Me, Until That One Evening

When Dad Died, He left a Haunting Message That Reemerged Just Now

My Father’s Sly Trick About Smoking That Saved My Life

Encounters with Fame 2.0

His Name Was Edgar. Not Ed. Not Eddie. But Edgar.

My Encounters With Famous People and Someone Else

The July 4th I Saw More Fireworks Than Anyone Ever