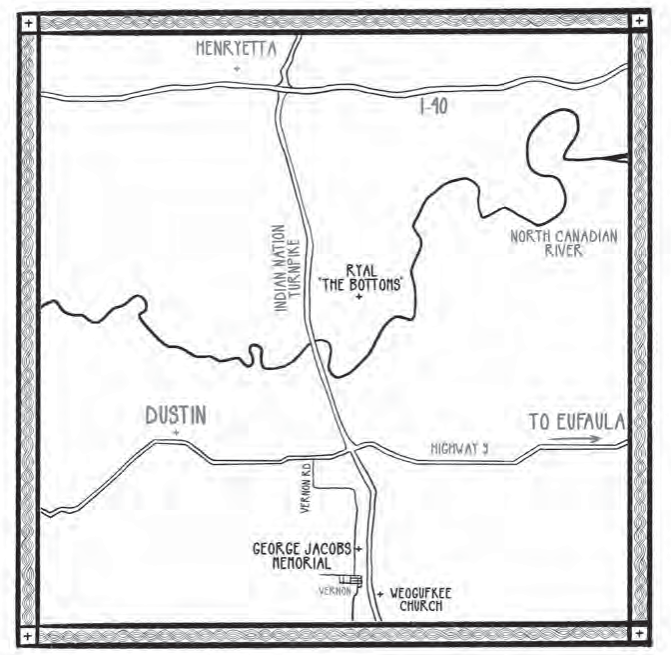

The Indian Nation turnpike is a four-lane highway cutting north to south through the bottom right corner of Oklahoma. On a cold day in November, I’m on the highway headed south. Just after Henryetta, the exit dumps me onto a shiny two-lane blacktop. After a mile, between the trees and the fence posts, I see a narrow opening on the left. Having pieced together the location from press coverage, court records, and word of mouth, I think I know where I’m going. The legal name for the road is N 3980, but everyone calls it Vernon Road, after the small town it leads to. The stereotype of Oklahoma, from musicals or Westerns or just plain ignorance, is of a land that is flat and dry. But that’s true only for the western part of the state. The fingertips of the Ozarks stretch into eastern Oklahoma, and in the spring and summer months the landscape—dotted with hills, rivers, and creeks—turns verdant. People call it Green Country.

Article continues after advertisement

It’s fall, and the sides of Vernon Road are deep and muddy, so I drive down the middle. I’m going parallel to the interstate now—the hum of the highway still audible—but on this road there is no traffic. After two big curves and a hill, the road stretches out flat and straight in front of me. The gravel is the color of faded rust, a burnt orange teetering on beige. I pass a Muscogee cemetery on the left, then a little yellow house, before reaching a spot on the road between the cow pastures and the trees that looks like any other spot except for one thing: a large, metal, white cross. The cross stands with a lean in the ditch. Garden stones have been placed in a circle around the base. The white paint is chipping and rust curls around the edges, but in faded letters I can still read the name George Jacobs.

George Jacobs memorial

It was a few days after the murder, in the summer of 1999, when the Jacobs family came to his house. Over twenty years later when we speak, Anderson Fields Jr. can’t remember exactly who it was, maybe a sister and a nephew. Probably through small-town talk, Anderson figures, the Jacobs family heard he was the one who found George. They wanted to put up a cross where their loved one had died, and they wanted Anderson to show them the place. And so he took them. At the time, it was an otherwise nondescript section of dirt road, except for one undeniable mark: blood. There had been so much of it, it stayed for months. “Even after it rained, you could still see that spot,” he told me. “After a while, it started to look like an oil stain.”

Many of the most important legal decisions about tribal land and sovereignty come from surprising places.

The cross commemorates George Jacobs’s life. But it also marks the exact location of his murder—a fact that would become crucial evidence in the appeal of his killer. That appeal would eventually go all the way to the Supreme Court. Under US law, tribes occupy a precarious legal status which often makes it difficult for them to bring cases on their own behalf. As a result, many of the most important legal decisions about tribal land and sovereignty come from surprising places. Like this one, which started in 1999 as a small-town murder.

*

August 28, 1999, was Patrick Murphy’s last day as a free man.

It was a Saturday—his day off. He didn’t have big plans, just helping his cousin move some furniture. Patrick woke up, took a shower, and pulled a beer out of the chilled six-pack waiting in his cooler. He drank it—all six—while he waited for his cousin to show up. Except for a small sliver of road, the view from Patrick’s front porch was trees.

That summer, Patrick was working in Henryetta as a line lead at a factory that built filters for the military. He was thirty years old and had three children from a previous marriage who were supposed to be staying with him for the weekend, but were at his mom’s place a few hundred yards down the hill. His girlfriend was staying there too; they had been fighting.

Patrick’s trailer, as well as his mom’s house, sat on the family’s land, a spot relatives still call the “home place.” “It was all cousins [that] stayed down there,” one aunt told me. Even the generations that came and went before Patrick were buried in the yard. Tucked into a curve of the North Canadian River, people call the small community the Bottoms; some call it the Hole. The name you might find on a map—if it’s marked at all—is Ryal.

Ryal is a Muscogee (or “Creek” in English) community. The last treaty Muscogee Nation signed with the US government, in 1866, reserved over three million acres for the tribe—spanning eleven counties in Oklahoma. Some parts are urban, containing the city of Tulsa and its surrounding suburbs. But the southern half of Muscogee Nation’s treaty territory, including Ryal, is rural. In these isolated communities lies the heartbeat of Muscogee culture. It’s where elders still speak the language, where Creek Methodist and Baptist churches stand, and where, on Saturday nights, people still dance at Muscogee ceremonial grounds.

Ryal was small enough that the Murphy kids could walk everywhere: between relatives’ houses, to the Ryal school, and to the local Creek Baptist church, Hickory Ground #1. When the grown folks were visiting, children were not allowed to listen or interrupt, so they played outside. The cousins spent those days cutting through the woods to the ball field, the basketball court, or another relative’s house. They built makeshift go-karts and raced them down the big hill that led to the river bottom. Only when called did they return home.

Patrick was raised by his mother, a full-blood Muscogee woman. His father, a Black man, hadn’t been around much. At Ryal School, Patrick was a star athlete. By the time he went to high school in Dustin, a little ways south, he’d honed in on basketball. A lot of cousins would move north to Henryetta, or even farther to places like Okmulgee or Tulsa, but after playing basketball for two years in junior college, Patrick moved back to Ryal.

By the time Patrick was sitting on his front porch that hot August morning, he had lived back home for almost a decade. Through an opening in the trees, he watched a car pull into the driveway. It was Mark Taylor, the cousin he’d been waiting on. Patrick threw a cooler of beer in the back of his green Chevy pickup truck, and both men piled in. After the cousins moved furniture and ate some barbecue, it was about six or seven o’clock. On a long, hot summer day the sun still sat high in the sky. They decided to go driving around. Not unlike the days they had spent roaming the hills of Ryal as kids on foot, except now they were roaming the back roads of McIntosh County by truck.

*

George Jacobs was older than Patrick, but from the same community. Since it was all family down there, George Jacobs’s grandma and Patrick Murphy’s great-grandma were sisters, which made them cousins in a way. In his half century of life, George had seen a lot, including a tour in Vietnam. After growing up in Ryal, he moved to Tulsa, where he worked as a mechanic rebuilding motors. There, he lived in a second-story apartment above his older sister. She remembered George coming downstairs every Saturday morning and saying “It’s time to eat” after cooking breakfast. “George was a younger brother, an easygoing guy who was always willing to help anyone if he could,” she would later say. (The Jacobs family did not want to speak about the case—one relative told me it was still too painful. Their comments about George are taken from court transcripts and victim impact statements.)

George Jacobs also spent that Saturday driving around with his cousin, also named Mark. George and Mark Sumka met up that morning on the Okfuskee-Okmulgee county line and decided to drive around in George’s black Dodge sedan. It was a normal thing to do on the weekend—backroading, visiting friends, and dropping in on relatives. Until nightfall, the Dodge sedan would meander back and forth along the four-lane Indian Nation Turnpike and the braided curves of the North Canadian River.

One of their last stops was George’s mother’s house, where George grew up. Down in the North Canadian River bottom, the house sat at the dead end of the same county road that went past the Murphy place. The matriarch of the Jacobs family was a lifelong member of Hickory Ground #1 Baptist Church and a homemaker who liked to garden, can fruit, and hand-stitch quilts. But she was in her seventies now, and the house was getting run-down. That day, George told his cousin he was thinking about moving back home. He wanted to help his mom fix the place up.

When night fell, George and Sumka took back roads down to a little country bar. At about 8:30 or 9 p.m., they sat down and ordered sandwiches. Mr. G’s bar sat in an old, rock building that had once been the post office for Vernon, Oklahoma. The handful of streets in Vernon, which is about nine miles south of Ryal, are named after the Southern states from which its early residents fled: Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama. As Oklahoma was becoming a state, Black people saw it as a potential oasis from the violence and segregation of the South, and they founded over fifty all-Black towns there. Vernon is one of thirteen that still exists. In its heyday, the town hosted a grocery store, hardware store, cotton gin, cafés, a syrup mill, and a hotel. Today, the only public establishments left in Vernon are churches.

By the time they finished their sandwiches, George was pretty drunk. After Sumka helped him into the passenger seat of the Dodge sedan, George passed out. Sumka took the keys and drove back north on the only road out of town: Vernon Road.

*

By the summer of the murder, Patrick and his girlfriend, Amy, had been together for five and a half years (her name has been changed here). According to Amy, Patrick would get jealous over little things, like if Amy talked to other people at work. If she read a book, Patrick would ask her “what was more important, my book or him,” she remembered. But the biggest thing that made Patrick jealous was George Jacobs. Amy had dated George for three years and they had a child together. That summer their daughter, Megan, was nine years old. As an adult, Megan remembered going outside when Patrick would beat her mother.

The Thursday before the murder Amy had gone into town to apply for a job. When she got home, Patrick accused her of going to see George. According to Amy, she and George no longer spoke. But Patrick didn’t believe her. He told Amy she should go back and live with George if she wanted. As the fight escalated, Patrick threatened to kill George Jacobs and his entire family. He said he was “going to get them one by one.”

Driving around that Saturday, the first relative Patrick and Mark Taylor dropped in on was a young man named Billy Jack Long. Billy Jack was the baby of all the cousins and that summer had just turned eighteen. He wanted to go out riding with the older men. “There’s no room for kids in this truck,” Taylor replied, knowing he and Patrick had been drinking. But Patrick and Billy Jack insisted. “He looked up to Pat a whole lot,” Taylor later told me. “And I sure wish he [Patrick] hadn’t drug him down that road.” Later, as the three cousins watched a neighbor rope calves, Taylor remembered he had told his wife he would watch their kids that night. He went home, leaving Patrick and Billy Jack to meander through the dark night without him.

The southern half of Muscogee Nation’s treaty territory, including Ryal, is rural. In these isolated communities lies the heartbeat of Muscogee culture.

Katherine King spent that Saturday painting duck decoys at a factory in Okmulgee County, and after she got off, her eyes, along with everything else, needed rest. She was asleep when Patrick’s loud truck motor in the driveway woke her up. Lifting the blinds with one hand, she looked to see who was there and recognized the green Chevrolet (she and Patrick used to work together). Next to Katherine in bed was her boyfriend of three years, who, in the complicated relationships of their close-knit community, was George Jacobs’s son. Through a crack in the kitchen door, she asked Patrick what he wanted. “Is he here?” Patrick replied. It wasn’t a friendly question. Katherine told Patrick that if he didn’t leave she would call the police. But her fourteen-year-old son, Kevin, wanted to go out drinking and riding around with the older men. People who knew Kevin called him “Bear.” At first Patrick wasn’t sure he wanted the kid to come, but Kevin offered to bring his own thirty-pack. Patrick would later say he let Kevin tag along so he could save money on beer.

Map of Vernon Area

Map of Vernon Area

With Patrick behind the wheel, Kevin King and Billy Jack Long piled onto the long bench seat. Patrick knew a country bar he thought would let the teenagers drink. It was a little south of where he lived, somewhere in the small town of Vernon. By the time Patrick turned left on Vernon Road, it was pitch dark. He couldn’t see the road curve left, then right, or the view from the top of the hill before it stretches out straight and flat. He could only see the rhythm of trees and fence posts through the moving patch of headlight beams.

On the unlit dirt road Patrick saw another car coming toward him. When the car got close, Patrick recognized it; it was George’s black sedan. Mark Sumka, who was still behind the wheel, had known Patrick since the first grade, and slowed down to say hi. The two cars stopped in the middle of the road, their windows parallel. Patrick asked Sumka who else was in the car. When Sumka said it was George Jacobs, Patrick told Sumka to kill the engine. Scared, Sumka took off. On the narrow road, Patrick swung his car around and sped up. He passed the sedan, then made a sharp right, cutting Sumka off with his truck. Sumka slammed on the brakes. In a cloud of dust, three figures jumped out of Patrick Murphy’s truck.

Before Sumka could put the car in park, Kevin and Billy Jack pulled George Jacobs out of the passenger seat and started punching him. Bewildered, Sumka ran around the corner of the car, but Billy Jack punched him in the face, hard. Blood gushed from Sumka’s nose and he fell to the ground. The sounds of the fight and the red glow of taillights dimmed as he went unconscious from the blow. When Sumka came to, he was alone. Afraid, he started running—away from the men and the fight, and into the dark. He hid—about a hundred yards away, breathless and bloody. But as he stood there his fear turned to worry. What about George? By the time he walked back toward the headlight beams, it was too late. He saw George lying in the ditch.

__________________________________

From the book By the Fire We Carry: The Generations-Long Fight for Justice on Native Land by Rebecca Nagle. Copyright © 2024 by Rebecca Nagle. Excerpted courtesy of Harper, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.