If you were a young Black writer in America in the 1950s and early ’60s, it was generally expected that you would write about struggle. It could be the struggle to put food on the table, or the struggle to walk down the street under the specter of racist violence, or the struggle to maintain your dignity in a world that wanted to degrade you; but one way or another (at least in the mind of well-meaning white readers), struggle was almost a mandatory theme.

The same held true if you wrote as an out gay man. At that time, you were expected to write about inner struggle: self-hatred, defiance, darkness of heart. You might insist on the value of gay love, like Gore Vidal in The City and the Pillar or James Baldwin in Giovanni’s Room; and if you were sufficiently defiant, you could depict the underworld of hustlers, like John Rechy in City of Night. Indeed, more and more Americans wanted to read about people on the so-called margins.

What readers did not expect from a young Black novelist—certainly not one who was Black and gay—was that he should take his worth for granted, that he should shrug off the gay thing with nonchalance, or acknowledge racial hostility without a flash of rage, or that he’d choose the drawing room over the street, parody over satire, camp over tragedy, Rachmaninoff over the blues.

For its very lack of militancy, Ladies has to be one of the most unusual, most hopeful, and funniest novels to come out of the Civil Rights era.

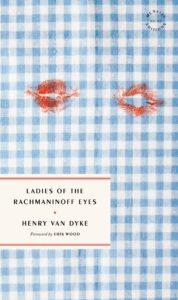

Then came Ladies of the Rachmaninoff Eyes, the first novel by my uncle Henry Van Dyke. Finished in 1961, rejected by a succession of publishers until finally published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux in 1965, Ladies is a comedy peeking out from behind the skimpiest of tragic masks. It tells of two elderly widows, Harriet Gibbs and Etta Klein, living together in the fictional Michigan town of Green Acorns.

The ladies have bonded over their decades before the dawn of the ’50s: “Harry” is Etta’s longtime housekeeper. They share a love for Harriet’s teenage nephew, Oliver; and an obsessive adoration for Etta’s dead son, Sargeant, who five years earlier—spoiler alert/open secret—committed suicide after he moved to New York and fell in love with a Black man. (The Klein family is white and Jewish; Harriet and Oliver are Black.) Enter one Maurice LeFleur, a self-proclaimed warlock, who promises to summon Sargent’s spirit from beyond the grave. Mayhem, as the saying goes, ensues.

As more than one critic noted, Ladies is an old-fashioned romp. A “light-decadent… confection,” in the words of the New York Times reviewer. According to the Kansas City Star, “Henry Van Dyke now gives us cause to hope that the Burroughses, Rechys, and Mailers may at last be succeeded by writers as intent upon the elegant phrasing of their messages as upon the messages themselves.” It’s true.

The fairy godfathers whispering in Henry’s ear were not Rechy or Burroughs—or Baldwin, either—but Noël Coward and Ronald Firbank. And yet Ladies found appreciative readers in younger queer writers including James Purdy and Iris Murdoch, on whom Henry harbored an enduring intellectual crush. The old tricks were being put to new uses.

*

Henry was born in 1928 in the small town of Allegan, in western Michigan. His mother’s family, the Chandlers, had arrived there in the 1850s as free people, when there was already a thriving Black community. The first Van Dykes came a few years later, on the eve of the Civil War. Like many families, Black and white, Henry’s forebearers had seen their fortunes rise with the tech boom of the early twentieth century, when corporations like Pfizer and Upjohn sprouted up around the railway hub of Kalamazoo.

Henry’s father, who went by Lewis, was a chemist; his mother, Bessie, an English teacher. In 1932, when Henry was four years old, they moved the family to Montgomery, Alabama. They had accepted professorships at the all-Black Alabama State Teachers College (later Alabama State University). In Montgomery they soon had two more children, daughters Barbara and Jackie.

The Van Dykes were prominent figures at Alabama State. Lewis would hold the position of Head of Arts and Sciences. The Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr., would officiate at Jackie’s wedding. Rosa Parks was a family friend. The children were also conscious of being set apart as transplants.

Although they attended the small, progressive Laboratory School on campus, Henry remembered having “only two playmates ‘suitable’ in my age range.” In his isolation, he turned to books. Bessie’s glass-fronted bookcase held more than the standard-issue Shakespeare, Milton, Keats, and Paul Laurence Dunbar. Henry was thrilled to discover Lady Chatterley’s Lover sandwiched between more anodyne books.

The college campus was a relative safe space even though Alabama whites made clear the boundaries for Black folk. I spent a childhood summer there, with my grandparents, after the 1963 church bombing in Montgomery that killed four little Black girls. I recall, as clear as this morning, Bessie warning me not to step off the porch for fear that I would be mutilated.

The Van Dyke children grew up in a kind of protective detention. As soon as Henry reached adolescence, Lewis began taking him on forays down country roads to view the dead bodies of lynched Black men. “Don’t look away!” he would command. This was meant to preclude “any ideas of having sexual traffic with a white girl.”

In fact, Henry was already—secretly and unhappily—attracted to other boys, and his perceived queerness was another source of anxiety at home. Lewis actively discouraged Henry’s love of piano and forced him to go out for the football team. Hoping to “outgrow” his homosexuality, Henry would have several encounters with girls and women. The first, when he was thirteen, took place with two boys and a girl “from the wrong side of the tracks,” and resulted in a pregnancy. The girl died from a back-alley abortion paid for by the three boys, who never spoke to each other again, and who kept the terrible secret. Henry’s parents never found out.

Soon after, the Van Dykes returned to Michigan long enough for Lewis to complete his PhD. Compared to Montgomery, Michigan was a kind of paradise to Henry: “I did not have to sit at the back of public buses; I did not have to drink from the tacky water fountain marked for colored only…I did not see the repressed rage within my father from being called ‘boy’ by a traffic cop.” Michigan also provided a refuge from his father’s scrutiny and disapproval. When the rest of the family returned to Alabama, Henry stayed behind. He finished high school in Lansing and Kalamazoo, living with his Chandler relatives.

Family life for the Chandler clan unfolded in the two-story Italianate house in Allegan that Poppa Chandler had built himself. Teenaged Henry observed all the bickering and indulgence that one might expect among cousins. As an adult, he would grow to be the family storyteller, the one who could bring the most dramatic and expressive of his departed aunts and uncles back to life.

Henry graduated from high school in 1945 and enrolled at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. He planned to study music and become a concert pianist. When Lewis demanded that he take premed classes instead, Henry retaliated by dropping out and joining the army. He would come back to the university later, on the GI Bill, to study on his own terms.

First, the army sent him to Germany, where he initially worked as a stenographer in the court martial system—a job he loathed—then he was recruited as second flautist to the (all-Black) 427th Marching Band, posted outside Heidelberg. In Heidelberg, he continued his musical education, taking private piano lessons under photos of his teacher, Franz Büchner, giving the Nazi salute.

The rigidity of these lessons shook Henry in his ambition to become a professional pianist, although he continued to play all his life. He loved Scriabin, Poulenc, Granados, Albéniz, Liszt, Rachmanino. always. Even at the end of his life, during his last weeks in hospice, he used paper keyboards to practice his fingering.

It was in the army that Henry started to write in earnest. He also started to explore his homosexuality, cruising Heidelberg’s notorious “Philosopher’s Walk” on the grounds of the old castle. There, he felt empowered. He was part of a victorious army among vanquished people, the reverse of his experience in white supremist Montgomery. His natural beauty, and the rarity of being Black in an ocean of whites, lent him an exotic allure. Henry returned to the University of Michigan in 1949, this time majoring in journalism. He wrote for the campus literary magazine and finished a novel, which won a college prize, although he never tried to have it published.

In Ann Arbor, Henry found a coterie of like-minded friends, most of them Black, most from the South, most from well-off families, all homosexuals. They relished commenting on classmates and movie stars and avidly musing about the sexual appetites of men who caught their eye.

In his own words, Henry found Ann Arbor “offered everything emotionally necessary…great concert artists…lectures…sensibilities both sweet and belligerent…sex…books…lieder.” He thrilled to the torch songs of Édith Piaf, Mabel Mercer, and Bobby Short, and to the high modernism of Gertrude Stein and Virgil Thomson, whose Four Saints in Three Acts became a talisman.

White readers were not used to finding Black characters treated with the same irreverence, neither more nor less, than whites.

Henry’s bohemian Ann Arbor also provided a cocoon for him at the height of the Civil Rights Movement. He followed the 1955–56 Montgomery Bus Boycott at a distance, through what he and his sisters called Bessie’s “Letters from the Front.” For the thirteen months the boycott lasted, Lewis woke every morning at four o’clock to drive domestic workers to their jobs, returning just in time to shower and assume his administrative duties by eight o’clock.

Bessie baked corn muffins for the riders. It is striking to me—it was striking to Henry, looking back—how completely he eschewed such current events in the fiction that he published in the campus magazine. “Perhaps I was running away,” Henry later wrote. “This path, this vision, this lack of militancy carried straight on through to my first novel.”

*

I suggest that, for its very lack of militancy, Ladies has to be one of the most unusual, most hopeful, and funniest novels to come out of the Civil Rights era. It is also unusually brave, for it is deeply autobiographical. The hero, Oliver, is clearly a Portrait of the Artist as a Gay Black Teen: undeclared in his sexuality, but queer to anyone with a clue. (The cluelessness of the people around him is a source of comedy throughout.)

The ladies themselves are drawn directly from life, based on Henry’s aunt Dayetta Chandler and on the real-life widow of a local executive. The setting offers an idyll—to use Henry’s word, a “vision”—of inclusivity, where racial inequity and homophobia exist but are not crushing. In Green Acorns, Blacks and whites, Jews and gentiles, mistresses and servants, are able to annoy, love, despise, and lust after each other as individuals.

Sexual identities are a matter of harmless confusion; the supposed “tragedy” of interracial or homosexual love is no more than a MacGuffin to animate a lighthearted, zany, not to say lunatic plot. When Oliver attempts a half-hearted seduction of a white (female) neighbor, nobody says or thinks anything about lynching. In Green Acorns, a Black boy’s love of Romantic music and French literature isn’t cause for derision; it means a free ticket to Cornell from Mrs. Klein, who treats Oliver like a second son.

Henry ven Dyke, courtesy Kent State University.

Henry wrote Ladies soon after he moved to New York City in 1958. Like many small-town writers before him, he found that New York gave him a clear-eyed view of the place he’d left behind. In New York he also found a new cosmopolitan tribe in piano bars, cocktail parties, and late-night cruising spots. He met many of his favorite musicians, including Bobby Short, who became a lifelong friend.

He formed more complicated friendships with Virgil Thomson and Carl Van Vechten, another elderly pair whose relationship he would fictionalize (to hilarious effect) in the sequel to Ladies, Blood of Strawberries (1969), set in the Chelsea Hotel. When Ladies couldn’t find a publisher, it was Van Vechten who advised Henry to rely even more on his ear for dialogue and his own glittering wit, to write the way he talked. Henry repaid that good advice by dedicating the book to him.

In New York, Henry could ferociously be his best gay self, and he was much recommended as a guide for visitors from out of town. So it was that he became friends with the flamboyant and very social Edward Montagu-Scott, Baron of Beaulieu; his wife, Belinda; and many of their visiting friends, including the British writer Geraldine van Wiedman.

Over a first lunch date at the Algonquin, van Wiedman asked to see the much-rejected manuscript of Ladies, then took it back with her to London, and to her editor at the publisher Hutchinson & Co. This editor, in turn, passed it to Roger Straus, the adventurous president of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, who happened to be in London, and who quickly wired Henry with an offer. Straus would go on to publish his next two books as well.

Ladies found its readers, but it’s fair to say Henry was never a hit with the general reading public. Really, his public did not yet exist. The foibles of his characters are universal; anyone with a family can relate; but perhaps this was part of the problem. White readers were not used to finding Black characters treated with the same irreverence, neither more nor less, than whites. Nor, perhaps, were they ready to laugh with a Black gay man as the author and star of an effervescent, epigrammatic farce.

Strange to say it now, but even many sophisticated people didn’t know camp could be a Black thing. (“Camp taste is a kind of love, love for human nature. It relishes, rather than judges, the little triumphs and awkward intensities of ‘character’…Camp is a tender feeling.” Susan Sontag, 1964.) In this matter, at least, I think America knows better today.

__________________________________

Ladies of the Rachmaninoff Eyes by Henry Van Dyke is available from McNally Editions.