Decades ago, as a young Shakespeare professor awash in a sea of books and articles about the playwright, I heeded the implicit academic injunction to “publish or perish.” I was expected to “join the critical conversation,” to produce similar scholarly work.

So I did. I wrote a book about the differing comic modes of Shakespeare and his contemporary, the poet-playwright Ben Jonson. But in the process of research and writing, I became so interested in the clear rivalry between these two writers, and in a related turn-of-the-seventeenth-century event known as the “Theater Wars,” in which they and other playwrights savagely mocked each other’s work before live audiences, that my fancies ran amok.

I couldn’t stop imagining debates that might have occurred between Shakespeare and Jonson; quarrels, over alehouse tables, about the nature and purpose of theater. I pictured street brawls between poets charging each other with not-yet-actionable crime of plagiarism, and fraught interviews between James I, the first Stuart king; and Jonson, who, despite his poet-laureate status, got jailed for mocking Scotsmen on the London stage.

These playwrights’ intertwined histories were so… dramatic! I can’t compare myself in imagination or talent to Lin Manuel-Miranda, but when I heard that Miranda, reading Ron Chernow’s biography of Alexander Hamilton, couldn’t keep from imagining Hamilton and Jefferson debating Treasury matters by means of a rap contest, I fully understood. Something similar had happened to me.

When it hit me that a clownish, country-yokel character in a 1599 Jonson comedy was in fact a parodic figure of Shakespeare, I knew the “Theater Wars” were calling for a new kind of description—not a scholarly but a fictional, or at least, fiction-ish, medium. I’d gone the academic route. Now it was time to have fun. So I wrote my first novel, Will, and gave those crazy playwrights a local habitation and a name.

Since then, I’ve kept up the game, writing “twisted” versions of Shakespeare’s plays (e.g., retelling The Merchant of Venice from the women’s perspectives) and further fictionalizing the Shakespeare family. My most recent novel, The Owl Was a Baker’s Daughter, charts the adventures of Shakespeare’s youngest child, whose remarkable span of years took her from the reign of the last Tudor through the Stuart era and the chaos of the English Civil War and on into the Restoration period.

To feed the fantasies, my reading has widened to include accounts of the Tudor and Stuart monarchs, biographies of Shakespeare and his contemporaries, studies of early-modern European culture and theater history, and—not least—others’ imaginative adaptations of Shakespeare’s plays.

The truth is, for good or for ill, that Shakespeare’s own life is largely a blank, and the clues we have about who he was and how he lived can only be found in the “shreds and patches” of official historical records (to borrow a phrase from Hamlet). We lack Shakespeare’s letters, his journals, even any document written in his own hand.

But it really doesn’t matter, because we have his works—one hundred fifty-four sonnets and thirty-seven plays, full of as much color and life as a Renaissance fair. The list of recommended books that follows therefore points, in no particular order, to what are, in my opinion, some of the last hundred years’ most engaging and provocative fictional works inspired by Shakespeare’s plays, as well as a Shakespeare biography or two, and one incomparable short story.

*

Best Hamlet-Based Novel in Which Ophelia Barks

David Wroblewski, The Story of Edgar Sawtelle

There are so many, many choices in this category, but mine is David Wroblewski’s The Story of Edgar Sawtelle, a highly original, well-told tale of a deaf-mute boy who raises hounds. Like Hamlet, he can’t speak his dark secrets to anyone but us, and his friends and family members only partly know him.

Ophelia? She’s a dog. Don’t laugh. In this book, the domestic situation is appropriately sinister, the account of a dog-breeding enterprise imaginative, and—this from someone who’s almost as far from being a dog person as you could possibly get—the description of dog-Ophelia’s death is intensely moving.

In my experience no stage depiction of mad Ophelia (or rendition of Gertrude’s account of Ophelia’s suicide) has come close to it for poignancy.

Best King Lear Adaptation in Which Both Lear and the Fool Bark

Richard Adams, The Plague Dogs

Continuing, per accidens, with the canine theme, one of the most surprising as well as loosest Shakespeare adaptations I’ve come across is Richard Adams’ The Plague Dogs. It’s one of those books—a bit like Sawtelle, but more so—in which the fact that it is an adaptation of Shakespeare creeps up on you, and in fact might not be noticed by one more familiar with Shakespeare’s plots than with his dialogue.

The book isn’t for the fainthearted. It begins with graphic scenes of animal torture in a British lab, an instance of Adams’ lifelong commitment to sparking sympathy for animals through his writing (which began with Watership Down). Two dogs escape from the horrid lab straight into the hills, where they endure difficult adventures and their own fraught version of Lear’s famous storm scene.

The novel is full of lines from Shakespeare, but the most striking ones come when Adams applies the anguished complaints of Lear’s suffering heroes to the plight of his own. It’s almost as harrowing a read as Shakespeare’s tragedy, but, unlike in Lear, there is light at the end of the kennel.

Best Book of Poetry Based on a Shakespeare Play

W.H. Auden, The Sea and the Mirror

The number of candidates for “Best Shakespeare Poem” would be truly overwhelming. They would include, for me, Borges’ haunting short verse, “Macbeth”: “Our acts perform his endless destiny. / I killed my king so Shakespeare / Could plot his tragedy.” (That’s the whole poem.)

Also strong in the field would be Edwin Morgan’s beautiful “Instructions to an Actor,” forty-five lines addressed by Shakespeare to a boy playing Hermione’s statue in The Winter’s Tale. (“You move. You step down, down from the pedestal”—I’m verklempt.)

But I consider the best book-length poetic response to a Shakespeare play to be W. H. Auden’s The Sea and the Mirror. In this series, he gives imaginative voice to several of The Tempest’s characters. Ariel speaks to Caliban, Prospero to Ariel, Caliban to us.

Auden seizes on the play’s conceit that these figures represent types of art, and the wizard Prospero the consummate artist or poet. Like Prospero, and perhaps like Shakespeare himself as he neared his end, in one poem, Auden uses poetry, that “unfeeling god,” against itself. Regretfully, heartbrokenly, and heartbreakingly, Prospero forswears art, a magic mirror that “changes nothing,” as Auden famously stated elsewhere.

If you don’t agree with that judgment (and I don’t), still, the poem, enchanting to disenchant, compels you to defend what you think, and lets you understand why, at the end of The Tempest, Prospero apologizes to the audience.

Best Horrifying Adaptation of The Tempest

Aldous Huxley, Brave New World

Shakespeare’s last play, The Tempest, has undergone more adaptations to more media than any other Shakespeare play. It’s shown up everywhere from post-colonial theater (see Aimé Césaire’s Une Tempête) to science fiction movies (see Fred Wilcox’s Forbidden Planet) to modern poetry (see Auden’s work, described above).

But one of the first, and most disturbing, applications of Shakespeare to modern fiction was of course Aldous Huxley Junior’s Brave New World. In place of Shakespeare’s magic island and his mage Prospero’s relatively benevolent wizardry, Huxley’s novel, first published in 1932, offers a dystopian futuristic society in which magical arts become horrifying technological achievements: sexless reproduction guided by genetic engineering; advanced machines for human transport.

The culture is governed by industrial titans who are worshipped. (Caliban’s, Trinculo’s, and Stephano’s “freedom” song is replaced by a trio of businessmen piously chanting the praises of Henry Ford.) The book is both funny and chilling, not least in the veracity of some of its predictions.

Best Fictional Adaptation of Macbeth

Dorothy Dunnett, King Hereafter

While Macbeth has seen numerous film adaptations, both strict and loose, the play has shown up as a novel fewer times than you might expect. In my judgment, Dorothy Dunnett’s King Hereafter is the best fictional Macbeth adaptation for those who appreciate eloquence as much as they do actual medieval history. Dunnett’s book is massive, and the complexity of character names and interrelationships rival those of the great Hilary Mantel’s matchless Cromwell trilogy.

So this book—based as much on historical chronicles as on Shakespeare’s play—may appeal most to readers already somewhat versed in eleventh-century British history. (I notice that one reader has provided an on-line character guide. Sometimes I like the Internet!)

The complexity is worth it, as we follow the brutal progress of a young Orkney Islander and his scary female partner, making their bloody way towards the throne—and not particularly enjoying it once they get there. As Borges wrote, “I killed my king so Shakespeare / Could plot his tragedy.”

Best Fictional Adaptation of Hamlet Which Excludes Hamlet

John Updike, Gertrude and Claudius

John Updike’s Gertrude and Claudius is not, strictly speaking, an adaptation of Shakespeare’s play, but a prequel to it. Mining, as did Dunnett, some of Shakespeare’s own sources, Updike relied partly on Saxo Grammaticus’ twelfth-century saga of Amlothi for details about the characters on which his Danish king and queen are based.

We meet Hamlet Senior in the flesh (rather than as a ghost), and get to know some secrets that the play keeps hidden: like, exactly how long has Gertrude been fooling around with her late husband’s brother? Updike’s eloquence is consistent, and it’s fascinating to assess the character of Hamlet—who, when on stage, won’t stop talking to us—from the kind of partial, side view first presented (more comically than here) by Tom Stoppard’s play Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead.

In Updike’s work as in Stoppard’s, Hamlet is mostly absent, a mournful and silent young man when he finally appears. The focus is on Claudius and Gertrude, and their mutual obsession. An unforgettable scene is one in which Claudius crawls through mud and worse into a barricaded garden, to perform the murderous deed to which Hamlet is aftermath. We already know what’s going to happen, but Updike’s writing compels us to turn the page.

Best Short Story about Shakespeare Himself

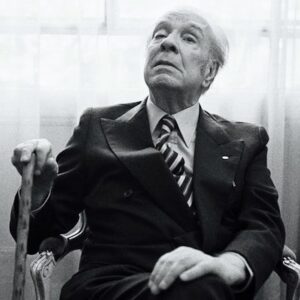

Jorge Luis Borges, “Everything and Nothing”

Most Shakespeareans, as well as most normal folks, would agree there’s no contest. The best fictional treatment of Shakespeare’s own life is a page and a half long. It’s the microcuento, or very short story, by Jorge Luís Borges entitled (in English, even in its original Spanish version) “Everything and Nothing.”

I won’t spoil this already-short story by describing it in too much detail. I’ll only say that in his mythical, semi-magical mode, Borges has managed to capture the eternal mystery of how and why a bourgeois tradesman’s son became that towering ghost of English letters, the creator of countless colorful dramatic characters who—as the above list attests—have haunted our literature ever since.

The short story can be easily found, but it’s worth reading it among Borges’ other fictions, quite a few of which (like “The Theme of the Traitor and the Hero”) also have much to do with Shakespeare’s plays.

Best Shakespeare Biography

Russell Fraser, Shakespeare: A Life in Art

The best Shakespeare biography I’ve encountered that is both entertaining and scholarly is Russell Fraser’s two-part one, which divides its focus and Shakespeare’s life into two parts. The first book is Young Shakespeare; the second, Shakespeare: The Later Years.

Without fabricating events, or performing impossible feats of mind-reading in the Shakespearean household, Fraser yet provides a lively account of all the known members of Shakespeare’s family and recounts as much as can be known about his home life and London career. For anyone interested in separating the slim facts from the myriad fictions about Shakespeare, these two books will answer.

Best Book on the Question of Why People Keep Asking Whether

Shakespeare was Shakespeare

James Shapiro, Contested Will

Last in my catalogue is a terrific book by noted Columbia Shakespearean James Shapiro, whose Contested Will deserves to be grouped with Borges’ microcuento “Everything and Nothing” as an answer to the question, not “Who was Shakespeare?” (as the title slyly suggests), but “Why can’t people just accept that Shakespeare was Shakespeare?”

Shapiro takes on the global urban legend that the Earl of Oxford, or Christopher Marlowe, or Francis Bacon, or Queen Elizabeth, or an intergalactic time traveler, or anyone but William Shakespeare himself, was the real author of Shakespeare’s plays. In an account which will fascinate those interested in literary and theater history, Shapiro shows that it wasn’t until a couple of hundred years after Shakespeare’s death that anyone thought to propose that the Bard wasn’t really the Stratford man.

And he shows why. Why, that is, it was two centuries before anyone thought to question Shakespeare’s identity. For, as Shapiro makes clear, the Bard was, indeed, the Stratford man. Get over it, Oxfordians. And, Shakespeare fans, enjoy!

______________________________

The Owl Was a Baker’s Daughter by Grace Tiffany is available via Harper.