Mary Wood didn’t want to provoke another controversy like the one that led to calls for her to be fired at a school board meeting last year.

She was reluctant to reintroduce Ta-Nehisi Coates’ memoir, “Between the World and Me,” to her Advanced Placement language arts class because her previous lesson was so controversially shut down in the spring of 2023, pulled by administrators after the writer’s recounting of being Black in America had at least one student feeling “ashamed to be Caucasian.”

But despite concerns that teaching the book violated a state ban on teaching concepts related to “critical race theory” and the strong reaction against it from some members of her community, the Chapin High School teacher felt that she had to try to teach the book again.

“It’s a good book, and it didn’t hurt anybody,” she said in a recent interview with The State. “A book can’t hurt a community, even if people try to make it sound like it’s something nefarious.”

This time, she would dot every “i” and cross every “t.” She made sure everything she did was lined up, approved and announced ahead of time. No parent or administrator would be able to say they didn’t know exactly what she was planning to do.

Wood was committed to teach “Between the World and Me” not only because she thought it would be valuable for her students, but because she is concerned about the future of teaching.

The state’s prohibition on race-related topics remains in effect, and the state recently dropped an AP African-American studies course from the curriculum. Under S.C. Superintendent Ellen Weaver, elected in 2022, the Department of Education also has moved to centralize the approval of books that can be used in the classroom and potentially remove a challenged book from being used statewide.

“It’s no lie, it’s no secret that racism and inequality exist,” Wood said. “Why would you want to prevent the discussion? It’s dangerous.”

Last year’s controversy around Wood’s lesson plan brought national and international attention to the Chapin-area school district, when her lesson was stopped prematurely and copies of the book taken back after some students wrote to Lexington-Richland 5 school board members complaining that the lesson made them uncomfortable.

“These videos portrayed an inaccurate description of life from past centuries that she is trying to resurface,” one student said at the time. “I understand in AP Lang, we are learning to develop an argument and have evidence to support it, yet this topic is too heavy to discuss.”

Another wrote that “I am pretty sure a teacher talking about systemic racism is illegal in South Carolina,” referencing a state budget proviso that prohibited the teaching of various ideas related to race, including those broadly associated with “critical race theory,” an academic framework used in high-level university courses for studying how the development of laws and public policy contribute to racial inequity. In popular discourse, though, the term has come to be applied to most discussions of race or racism in K-12 schools.

‘I don’t belong’

The aftermath of the controversy was hard for Wood, a Chapin native whose father was principal of the high school where she now teaches.

“Some parents pulled their kids from my classes,” Wood said. “It was not well-received by a lot of people. I had people tell me I don’t belong in Chapin, which is a weird thing to hear when you’re from here.”

But as her case received public attention, she also received an outpouring of support from people as far away as Alaska, Canada and France. Invitations to speak about her experience rolled in. She learned that many people supported her in an educational fight that, she worried, many teachers aren’t willing to talk about publicly.

“There are so many who are afraid to speak up,” she said. “I want to shed light on things for folks who are not aware.”

At the end of the 2022-23 school year, Wood wasn’t sure if she wanted to return to the classroom for another year. By the time summer break was over, she had made a different decision: She needed to teach Coates’ book again.

She spoke to an attorney, got the guidance of her new principal, Ed Davis, and discussed the district’s policies and procedures with her department chair and friend Tess Pratt, including making a plan to teach counterexamples that would challenge Coates’ conclusions.

“I followed expectations, I planned it out, I shared it in the syllabus before the semester began. And I gave students a chance to opt out,” and complete a different assignment instead, she said, “and none did.”

SC teacher’s racism lesson was shut down by book ban. But she’s still talking about it

The lesson plan did receive one complaint from a parent after she had started teaching the spring semester, Wood said, “and I had to fight for three weeks to keep teaching it, because I had done all I was supposed to do.”

In a statement, Lexington-Richland 5 Superintendent Akil Ross said controversial material is used in AP courses for discussion purposes, as long as it is presented in a balanced manner.

”The book ‘Between the World and Me’ has not been banned in our district,” Ross said. “Supplemental materials, including this book, may be used in a classroom setting if they are based on the content standards … (which) ensures that ultimately the teacher will not attempt, directly or indirectly, to limit or control students’ judgment concerning any issue.”

Start to doubt

Even if she felt she was in the clear legally with her lesson plan, the memory of last year’s class, and the complaints it had generated, made Wood feel inhibited in what she could say.

“It’s hard to discuss an interpretation, because you don’t know if you’re being recorded or it’s going to be taken out of context,” she said. “It kind of flattened discussion in the class, because I didn’t want someone to say, ‘She said this, she’s indoctrinating us.’”

The point of the class is to prepare students who will soon be headed to college for how to engage with new and different perspectives and beliefs they don’t necessarily agree with. But Wood said she felt the classroom discussion wasn’t able to do that if she felt she couldn’t share those differing perspectives.

“I would have been more bold,” Wood says now. But when her lesson plan received so much pushback from people who not only disagreed with it, but also believe she’s fundamentally biased, was breaking the law and should lose her job, “you can start to doubt yourself, and it seeps into your life,” she said.

Coming into this school year and her second shot at the lesson on the Coates book, Wood wasn’t sure what the students in her class had heard about her at home or on social media before they came to class.

One day, a teary-eyed student came to her concerned that “you’re about to be fired,” Wood said. Another said he was told that “you’re a racist” for wanting to teach Coates’ book and that the author “hates white people.”

“I don’t think they know what racism is,” said Wood, who is white.

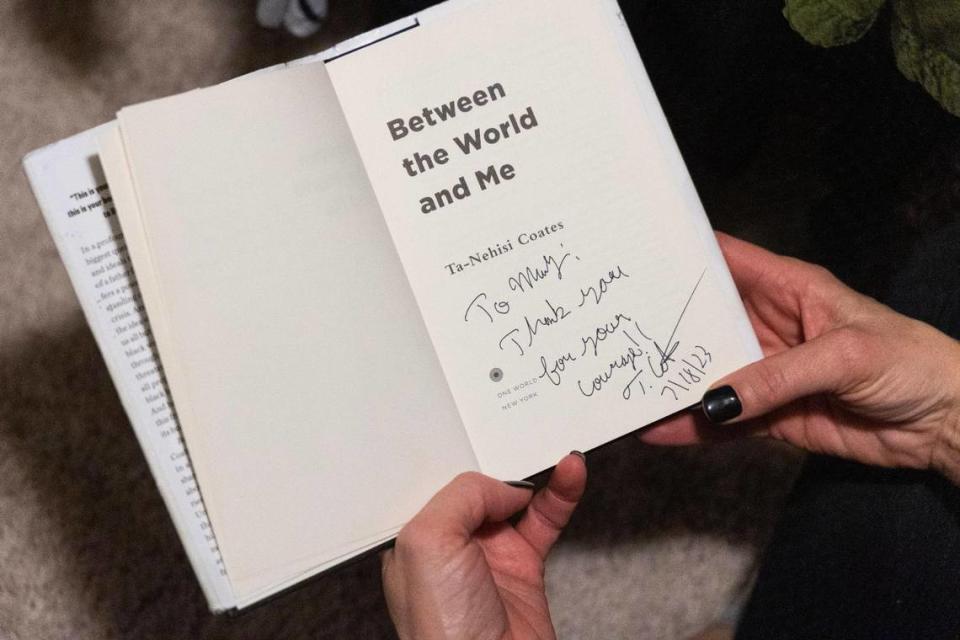

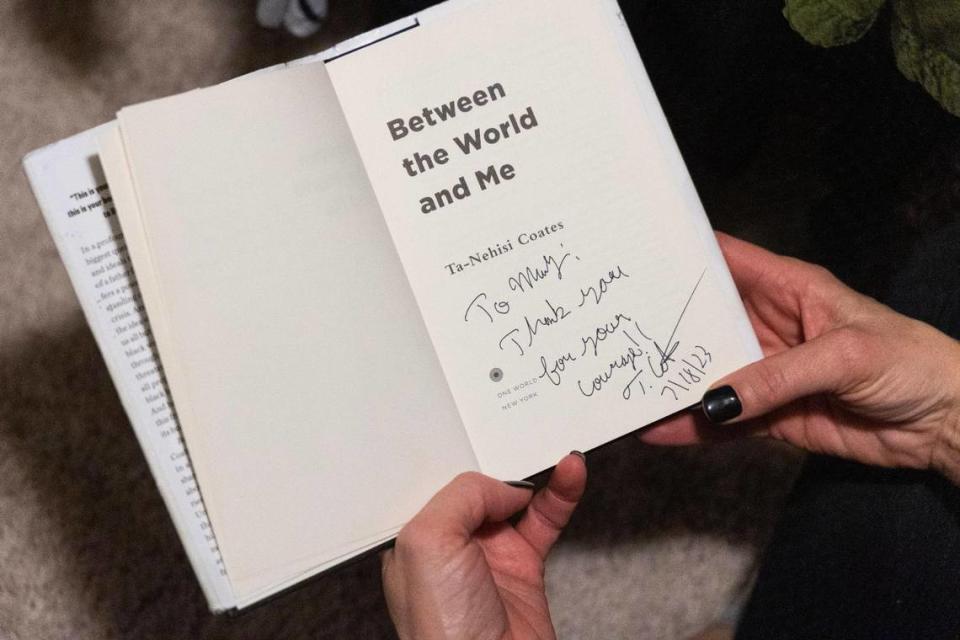

None of her students mentioned it, but Wood said she thinks it’s unlikely they didn’t know about the controversy that erupted over the same book last summer. The author even paid a visit to Wood and sat in on a school board meeting where members of the public spoke in support of Wood’s teaching, although he didn’t speak himself.

Coates is writing about the Lexington-Richland 5 controversy in his new book, “The Message,” publishing this fall. Among other reporting trips for the book, “he takes readers along with him to Columbia, South Carolina, where he reports on his own book’s banning, but also explores the larger backlash to the nation’s recent reckoning with history and the deeply rooted American mythology so visible in that city— a capital of the Confederacy with statues of segregationists looming over its public squares,” according to a blurb from the publisher, Penguin Random House.

One source of encouragement for Wood was the presence of her 16-year-old son, Summit, in her class this semester, something that she thought helped with the classroom discussion.

“It brought an element of humanity to me,” she said. “I wasn’t just a teacher, I’m Summit’s mom, so it established a more human connection. They could see me as more of a person.”

The reason she wanted to teach Coates’ book, she said, was the same as the purpose of the AP course itself — to teacher students how to critically engage with and respond to other people’s perspectives they may be unfamiliar with, even when they disagree with them.

“If you look at Chapin, it’s conservative, Christian, wealthy, and the world is bigger than that,” she said.

Instead of being taught how to engage with those outside perspectives, she fears students will learn the correct reaction to them is “to shut down that discourse and those relationships within the classroom.”